The Government, in line with our Australian cousins, is finally bringing in a new front of pack labelling system for all packaged food (the stuff at the supermarket). It’s a step in the right direction, but we desperately need more before the diabetes problem runs away with us.

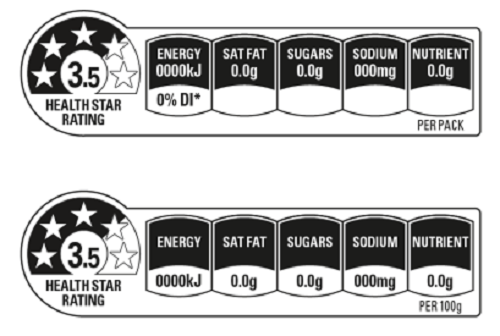

It’s taken three years, and the preferred approach recommended by nutritionists has been ditched along the way, but we finally have an agreed label that tells consumers how healthy a product is. The health star rating system uses a nutrition model to rate foods out of 5 stars – from a 1 star for complete junk like soft drinks (like school, no one likes to get a zero) through to 5 for plain yoghurt and wheat biscuits.

Why is this important? The Government’s response to the obesity and diabetes crisis we face is to say that what we eat is a matter of individual choice. Given that half of Kiwis say they don’t know how to eat healthily – and most of the other half don’t really know what they are doing either – people aren’t really making an informed choice at the moment. This isn’t helped by the mixed messages people get through the media and advertising. The health star rating system will (hopefully) help inform people over time.

Of course, this won’t change the way we eat overnight. People will still want to eat the same kind of food – so don’t expect frozen pizza to disappear overnight. What we do know is that this sort of labeling will influence people’s choices between similar products, so they are more likely to choose the healthier pizza option. The real benefits of this will become apparent when the food industry starts reformulating their recipes to make them healthier.

So a standard label on the front of food packaging, which informs people about nutritional content, is a good step forward. But there are a couple of problems with the Government’s tentative first step: it isn’t compulsory, and a standard label still doesn’t mean people will understand what they are eating.

The biggest hole in the proposal is that it is voluntary. Naturally this means that all the products for whom the star rating system is bad news will simply not display it. Soft drink manufacturers seem set to stick with their daily intake guide, which works for them because no one understands or uses it. The Government is loathe to make it compulsory because of the additional costs to food businesses – never mind the millions of dollars that obesity and diabetes are costing our health system already. The promise is that if uptake is ‘low’ then the Government will review making it compulsory in three years. Why wait?

The other problem is that people won’t understand this labelling system without an information campaign. There isn’t much evidence on the health star rating system, but it appears to be less effective at helping people identify unhealthy foods than the well researched alternative: the traffic light labelling system. Consumers intuitively understand the red light means a food is unhealthy, which is why the food industry pressured the Government into ruling out using traffic lights from the start. Of course the food industry dislike the connotation of a ‘red’ light – it means stop. The food industry never wants you to stop, even if you should.

So if the healthy star rating system is going to work, people need to be told what the stars mean, otherwise they might think 1 star is okay and 5 is great. The truth is that 1 star really means a food should be considered a ‘treat’ or very occasional food – in the once-a-month sense of the word rather than the everyday sense it has become. We need an information campaign to hammer this home.

One final concern is on the ratings themselves. Most labelling systems throw up some anomalies, however you have to wonder a bit when orange juice and flavoured (albeit low fat) milk get rated as healthier than full fat milk. The nutrition model behind the stars must be made available to the public so that it can be critiqued and improved, and most importantly so that we can work out the star ratings on the products that choose not to display them.

These glitches are not surprising – the Government is taking its usual position of looking like it is doing something while avoiding doing anything effective. That this would be the outcome was evident from the outset when the group was chosen to advise the Government on labelling. Half the group representatives were from large food companies, so the turkeys were never going to vote for Christmas were they?

So in all the labelling system is a step forward. Consumers should make sure they buy products with the star rating, that will encourage food companies to use the new label. The consumers should blacklist any food that doesn’t take it up. Any well-intentioned group would have made it compulsory from the start, so consumers will need to force the pace on this still.