Peter Dunne’ policies are often overshadowed by his very fine head of hair; and to be fair Associate Minister for Health’s ‘do’ is really quite striking. On this occasion however, we really should be admiring him for the sensible decision he has made that allows evidenced based policy to thrive with regards to national and local health issues.

Yesterday it was announced that later this year legislation will be introduced to the house to allow the decisions for fluoridating local water supplies to move from local body councils to District Health Boards. Hurrah! It is a move that both local councils and health advocates have been asking for years.

We like to celebrate the wins here at the Morgan Foundation, and give credit where credit is due. Last year this move away from local councils back to health was exactly what we argued should be happening, as it will likely help to improve the coverage of fluoridated water supplies in the regions that need it most.

Fluoridating water supplies is one very important action we can take that will have a large impact for minimal effort and resource investment, but it is by no means a silver bullet for our country’s dental problems.

Naturally there is opposition from the anti-fluoride brigade. Their main concerns are that by moving the water fluoridation decision to DHBs, individual’s democratic rights and consideration of the local conditions will be trampled on.

Lets deal with the democracy concerns first.

Moving Decision Making to DHBs still Allows for Local Input

As we discussed in our previous blog on this issue, local level decision making is more democratic, and we outlined how moving it to DHBs does not in any way remove that right. DHBs are elected for starters on their ability to make decisions about community health specifically, although it isn’t yet clear who in the DHB will make the decision. Even if the decision isn’t made by the elected Board, representative local surveys on people’s views and community consultation are more than feasible, as are citizen juries, and such information can be used to inform the decision making.

What we do know is that the current system is very undemocratic. We have seen interest groups influencing council decision making so heavily that in both Hamilton and this year in Whakatane after the council voted to remove fluoride they then did an about face and put it back in. The reversal in Hamilton occurred because the the community felt so strongly that this was the wrong decision, while in Whakatane a single councilor changed his mind on the science. So it is hard to see how democracy will be more poorly served by this move, and will probably be better served through more consistent weighing of the evidence by people with a better understanding of health.

On that note let’s talk about the consideration of local conditions in the decision-making.

DHBs understand local health conditions better than Councils

The latest systematic review on community water fluoridation noted a few things; the first is that water fluoridation is effective in preventing tooth decay in children but they also noted that the study base was old and needed updating – something we will get on to soon). They also noted that

“The decision to implement a water fluoridation programme relies upon an understanding of the population’s oral health behaviour (e.g. use of fluoride toothpaste), the availability and uptake of other caries prevention strategies, their diet and consumption of tap water and the movement/migration of the population.”

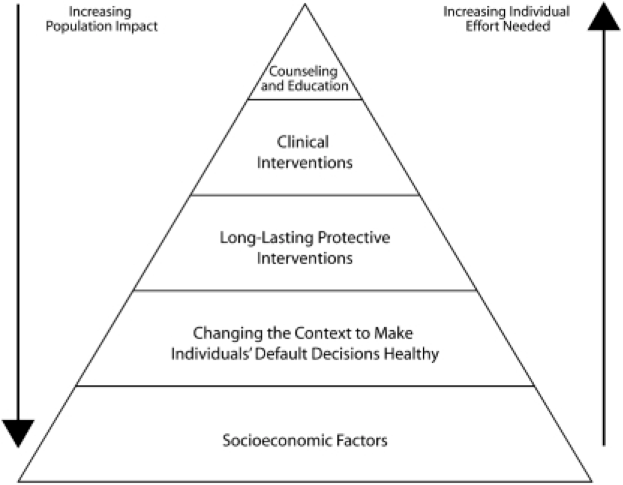

Such a statement is in-line with how the health impact pyramid works (see the box below). We need to understand what is going on in all the other areas that influence health outcomes in order to deliver the best most effective interventions.

Improving Health in a Population Requires Actions on Multiple Levels.

No one in health (or indeed anyone who knows about good policy development) argues that high-level legislative changes (i.e national policy, regulation, tax etc) alone will improve health. Though strangely people (usually those with a vested interest) argue that education and behaviour change interventions will work alone. But the truth is that no intervention works in isolation. The population health intervention pyramid forms the basis of how good public policy can be used to achieve an outcome (not just in health really). What we can see is that some interventions do require significantly more effort from the individual and from the health system. This means a higher cost and more resourcing effort to get the same outcomes.

What we do know already is that in many of the poorer communities in New Zealand other tooth decay prevention strategies struggle to get traction, diet is poor, and kids are mobile (though within poor communities- there are not thousands of poor kids moving into high income areas).

The Regional Public Health Services (who are part of each DHB) have a much better understanding of these issues at their local level than do the local councils. This is what they do all day every day- they consider the health of their local population, where it can be improved and what barriers are currently in place to achieving that. Therefore DHBs are in a much better position to consider the fluoridation of water supplies in context of their understanding of current behaviour affecting teeth in their region. This means better more informed decision-making.

The Potential to Develop the Evidence Base

One of the additional benefits to moving the fluoridation decisions to DHBs is the ability to better plan and implement studies on the effects of their activities. All policy and interventions that are run at a cost (even if it is small) to the taxpayer should have robust and high quality evaluation built in. Many working in DHBs and Regional Public Health Services have a much better understanding of this than those in local council.

The Proof is in the Pudding

So we shall see if moving the fluoridation decision to DHBs leads to improved outcomes for children in terms of tooth decay. If well implemented then it should and Peter Dunne should have much more to smile about than merely his splendid head of hair.