Last week was the official reinvention of Children, Young Person and their Families Service (CYFS). With the creation of Oranga Tamariki (also poorly named the Ministry for Vulnerable Children) the Prime Minster has said the Government is ” strongly committed to investing in these children [those in state care] at a stage where we can do a much better job with them”.

This is great to hear. Bill English then went on to say that:

“We have a fundamental obligation for the 5000 [children] in state care, then there is a wider group of up to 90,000 to 100,000 children who you would think are at risk and when we’ve got the system better dealing with them … then I suppose you could look at going broader.”

Unfortunately, this approach is totally topsy-turvy. It is going about things without reference to how families become “vulnerable”. This is ambulance at the bottom of the cliff stuff.

If the Government is committed to making this new Ministry really work for these children and their families – which means positive lives, with the freedom and opportunity to explore all their amazing potential and have a quality of life that they feel good about – then there are two simple steps to follow.

Step One: Prevention

The first focus of Oranga Tamariki, and indeed the Ministry of Social Development more broadly, should be a vigorous commitment to preventing any children ending up in state care. The highest quality evidence, which we have covered in depth in the book Pennies from heaven, tells us the following:

- When we say poverty is the problem in vulnerable families, what is actually going on is that the grinding stress from living with insufficient resources has become toxic.

- This stress breaks relationships and mental wellbeing and impedes decision making.

- This stress impacts children’s brain development and immune system, making them vulnerable as adults.

- This stress leads to family breakdown but does not stop the love families have for their children. To infer that all these children need is love ignores a huge body of evidence explaining why families and children do badly when they are poor. It has very little to do with a lack of love.

- What is most effective for individuals, families, whānau (and the economy even) is to use powerful policy tools to uncover the love (and the ability to act on that love positively) being smothered by poverty related stress

- What works most powerfully to do this is sufficient money without punitive conditions and paternalistic judgments. This approach is highly cost-effective.

So step one is do what works best to ensure families who are struggling under the toxic stress that comes from rising costs and precarious low-paid work are sufficiently supported to be great families.

Following prevention, we move to cure.

Step Two: Follow What Works for Children in Care

I have written previously about the lack of evidence that children are better off in state care. That is not to say we definitely know that children in families under intense pressure are better off staying with their families; more that we just don’t know whether the state does better (an absence of evidence). The lives of children in care are not what we would call flourishing ones by any measure. Abuse that children have experienced in care in New Zealand is simply the worst bit floating above the surface.

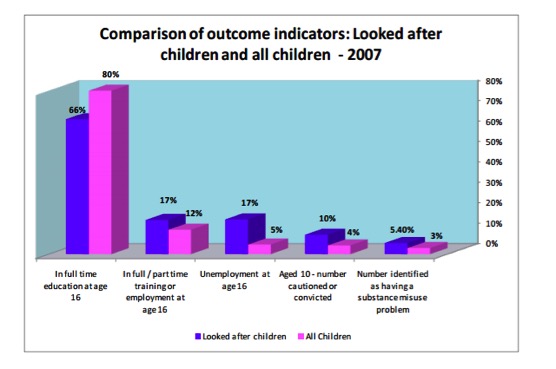

Here is some data from the UK showing just how poorly children in state care fare.

Source: NICE, UK

Children in state care In New Zealand might not be at risk of abuse from their parents (in some cases), but more often than not they are at risk of pretty much everything else. They are more likely to be homeless, be involved in the criminal justice system, have drug and alcohol problems, and experience poor mental health and unemployment. Judge Andrew Becroft, the current Children’s Commissioner, has spent years highlighting what he calls the “staggering and profoundly concerning link between children who have been in care and crime”.

What does work?

First, it would be useful to properly measure what actually happens to children in care. Our data systems to understand what is happening to children in care have been very poor compared with international best practice. For example, only 71% of children entering the former CYFS care got a baseline measurement of their health and wellbeing and none were followed up with a formal monitoring system. This is like running an experiment without bothering to measure what happens. (In fact, that is exactly what it is.)

As part of the commitment to good process, research and evidence, it is vital to hold an enquiry into what processes were in place and why they failed those children subject to appalling abuse in care over the years. When an experiment falls over, we need to know where it did so to amend our approach to follow methods that do work. I use the term ‘experiment’ in the scientific sense, because radically changing the conditions of a child’s life via an external intervention when you have no previous evidence on what the outcome will be is an experiment.

Second, accept that parenting and caring for these children is an expensive and complex job (which the Prime Minster appears to agree with), and that this requires significant skill and empathy. Children taken into the care of the state are incredibly exposed. They need significant additional support to experience the type of life we believe children in New Zealand should have. They need more than just standard parenting.

Research indicates that these children need intensive, skilled, professional care. Intensive care means much higher investment in training for staff training and foster parents, greater remuneration to those foster/interim parents dealing with the most vulnerable and challenging children, and a full team of skilled and capable support staff available to the parents and institutions now responsible for their lives. This includes social workers, psychologists, paediatricians, and other behaviour specialists.

Building an evidence-based culture in the new Ministry across all areas (which takes money and time) is key to following what works. Putting the wellbeing of children front and centre of all the Ministry’s work can make it a whole lot easier to build such a culture, because the outcome you are working towards is always crystal clear and nothing can be done without the effects on that outcome being clear.

So step two is to commit the Government (with sufficient funding and by building the right structures and culture) to delivering highly skilled work that research tells us is needed to improve the lives of children taken into care.

The Prime Minister is totally correct we cannot afford not to make this work. These babies and children who become the adults living in our communities need us to do so much better for them. All New Zealanders want these children to be OK; to live the most positive lives we can give them. It benefits not just the children but also all of us who want a thriving and flourishing society and economy. Let’s not lose sight of these values again by favouring populist and reactionary solutions. Two little steps are all we need.