Earlier this week the New Zealand Initiative (NZI) released their thoughts on inequality and specifically the role housing affordability has played in exacerbating the numbers. It’s good to see a business-funded think tank acknowledging that inequality matters – despite the fact that of late some measures (that exclude the affordability of accommodation) suggest it’s not getting any worse.

And on that the NZI authors pose the question of why – if it’s not getting worse – is newspaper coverage increasing? That’s not hard to answer and I will below. In short the answer is it doesn’t matter whether inequality is rising or not; the long-term persistence of some types of inequality weighs down economic growth.

A second point NZI makes is that inequality isn’t the same as poverty. This is totally correct and discussion should not conflate the two lest our thinking leads to simplistic and flawed policy responses. I’ll deal with that as well as I cover various drivers of inequality .

There are two main drivers of inequality and they have quite different implications:

- Inequality arising as the consequence of merit-based economic success, and

- Inequality that comes from leveraging market power; profiteering without providing anything of benefit to others. This can include anything from regulatory protection to exercising monopoly power right up to outright corruption.

The first is the type that traditionally economists have lauded as an acceptable part of a market economy (as it provides an incentive for effort), the second obviously is a bad thing. So in effect we cannot – without having first determined what type of inequality we’re dealing with – conclude that the inequality we observe is a good or bad thing. And remember there is also life-cycle inequality (on wealth at least older people have had more time to accumulate assets) and education-based inequality. If the population is ageing then one would expect wealth-based inequality to rise, if the education base is improving one might expect income-based inequality to fall – although I’ve been to plenty of economies where education delivers diddley squat to recipients, e.g.; Egypt.

What we can say is that inequality arising from market power should be addressed by ensuring all participants have equality of opportunity. Note as an aside, that the trend is for educational opportunities to become more skewed as a result of increasing inequality – ie; a self-reinforcing feedback exists.

“… recent experience from China to America suggests that high and growing levels of income inequality can translate into growing inequality of opportunity for the next generation and hence declining social mobility. That link seems strongest in countries with low levels of public services and decentralised funding of education. Bigger gaps in opportunity, in turn, mean fewer people with skills and hence slower growth in the future.” [i]

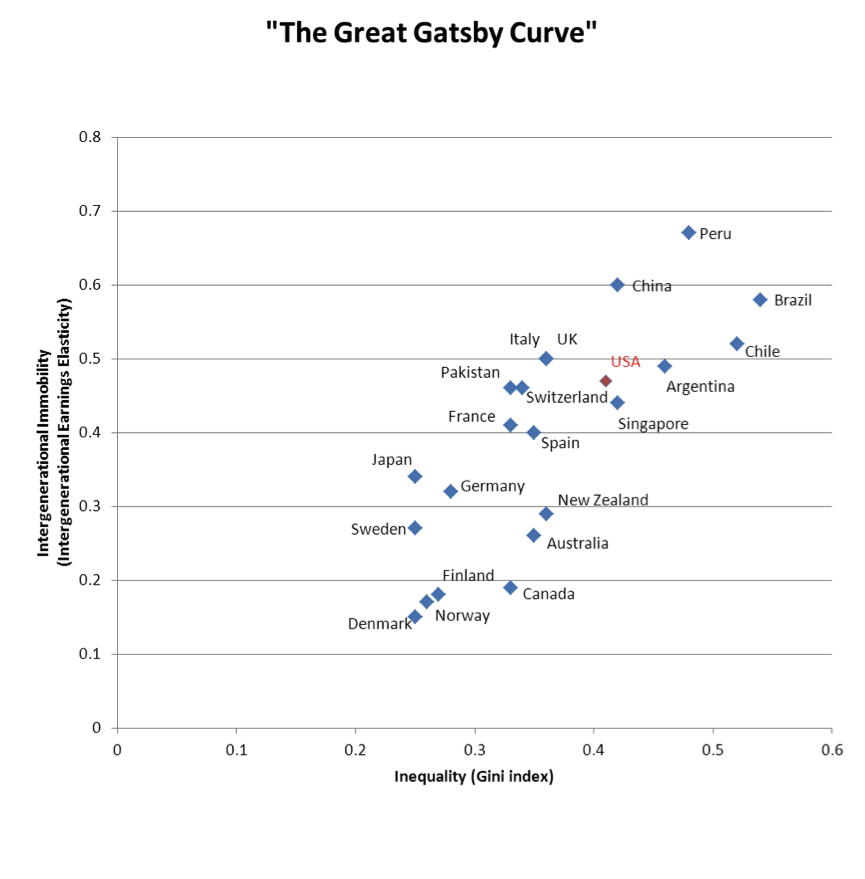

“Inefficient” inequality begets further inequality when the children of the lower social classes don’t receive the same opportunities as others and so can’t escape the social position they are born into. This in turn impedes economic growth, because they don’t fulfil their potential. “The Great Gatsby Curve” concocted by Canadian economist Miles Corak, shows the relationship between intergenerational social mobility and income distribution. The more inequality, the greater the degree to which it is passed on, the lower the earnings mobility across generations.[ii]

The conclusion that inequality has arisen because of merit, which underscores the acceptance of inequality as a necessary element of competitive economies (to which both Keynes and Friedman subscribed), does rely on the assumption that government ensures that all citizens are provided the basic services to be able to participate. There’s the rub. As Amartya Sen concluded, too often that doesn’t happen. His capability approach argues it is important to remove barriers to people fulfilling their (reasonable) aspirations.[iii]

For Sen, ‘poverty’ is more than the narrowly defined income deficiency, it is deprivation in the capability to live a good life – far more meaningful than the narrowly-defined metric around income. In his book Development as Freedom he cites development as ensuring three freedoms – political, opportunity (including access to credit), and protection from abject poverty. Poverty in his definition, includes lack of at least one of these freedoms.[iv]

And as the OECD has also concluded,

“Intergenerational earnings mobility is low in countries with high inequality ….The resulting inequality of opportunity will inevitably impact economic performance as a whole, even if the relationship is not straightforward.”[v]

So as well as State-funded access to education (including pre-school education and re-training) and healthcare, cash payments to the poor or the instigation of a Unconditional Basic Income (UBI) should be seen as tools for citizens to enable fulfilment of their (reasonable) aspirations. Vitally, the public sector’s role in underwriting income needs to be unconditional – because each individual’s aspirations are different and no government agency, no matter how well resourced, can possibly determine those aspirations better than the individual.

Finally it’s important to acknowledge that the evidence so far suggests that it’s when inequality rises due to poorer households failing to get income rises in proportion to those of the population generally (the median), that one can identify the need for correction. Importantly there is no evidence that increases in income of the highest earning groups that increase the gap over the general population, cause any harm.vi

So inequality can be growth-inhibiting, how much depends on the source of that inequality – whether it’s deserved or imposed, whether it becomes entrenched intergenerationally so power (market and political) is concentrated, and whether it arises because the growth in lower incomes is persistently lower than the growth in the middle incomes.

In New Zealand inequality rose dramatically as a result of early 1990’s reforms, reforms which directly whacked lower income people. That inequality persists and is worsening if you look at wealth inequality (property). It suggests New Zealand has work to do if we want economic growth to fulfil its potential. Acknowledging that “trickle down” has not delivered and ensuring there are opportunities for all, should be at the centre of policy now.

“… policies to reduce income inequalities should not only be pursued to improve social outcomes but also to sustain long-term growth. Redistribution policies via taxes and transfers are a key tool to ensure the benefits of growth are more broadly distributed and the results suggest they need not be expected to undermine growth. But it is also important to promote equality of opportunity in access to and quality of education. This implies a focus on families with children and youths – as this is when decisions about human capital accumulation are made — promoting employment for disadvantaged groups through active labour market policies, childcare supports and in-work benefits”.vi

[i] The Economist, 13 Oct 2012, http://www.economist.com/node/21564421

[ii] Miles Corak (2013), “Inequality from Generation to Generation: The United States in Comparison,” in Robert Rycroft (editor), The Economics of Inequality, Poverty, and Discrimination in the 21st Century, ABC-CLIO.

[iii] Sen, Amartya (1985). Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam New York New York, N.Y., U.S.A: North-Holland Sole distributors for the U.S.A. and Canada, Elsevier Science Pub. Co.

[iv] Sen, Amartya 1999 “Development as Freedom” Oxford

[v] OECD, 2011 “Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising”, OECD Publishing

vi Cingano, Federico “Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth” OECD 2014