The dairy industry in New Zealand decided some time ago that it preferred to pursue growth through increasing the volume of raw milk produced and specifically eschewed the notion that it would pursue the most profitable opportunities in the sector whether they were on-farm or downstream. It has made its bed and today we see the consequences of that. The industry is a cork floating on the waves of the commodity cycle and the swings and roundabouts of fortune and misfortune that such activity entails, is just business as usual. If it weren’t for the size of the sector, nobody would really care.

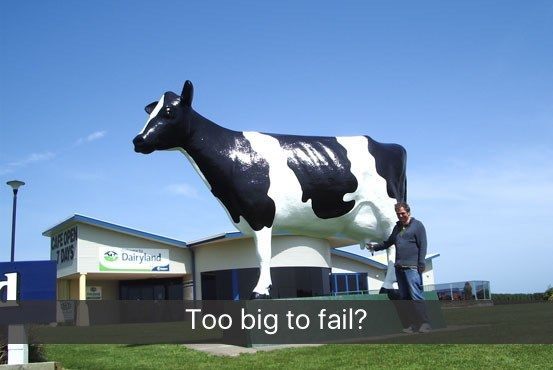

In 2016 our dairy industry retains its leverage over the country of being ‘too big to fail’. And with that comes all manner of baggage that politicians, bankers, and taxpayers have to deal with. This was a deliberate decision made at the beginning of this century when the industry mutated from a couple of large co-ops and the NZ Dairy Board to Fonterra. That transformation was ordered by government decree and overruled the advice of the Commerce Commission. We deliberately decided to make a company that would become too big to fail – the rationale being that New Zealand’s competitive advantage was in pastoral dairying, nobody could do it more cheaply and as the world demand for protein expanded we would make hay – feed more cows, make more money, feed even more cows.

Building such a large industry as a one trick pony pretty soon showed all manner of weaknesses. Returning all the profit to the farmer at one end of the supply chain rather than enabling investment to go where profitability was greatest, quickly resulted in the number of cows outweighing our ability to just feed them grass. The growth of dairy farming drove the price of land wild, further driving the need for intensification and with that the demand for food supplements – most of which were imported. Of course we have no competitive advantage whatever in making milk from imported feed and then sending that milk back to overseas markets. The cost of production rose.

Meanwhile overseas, the growth in feedlot dairying has been predictable as the price of raw milk rose in line with the increased demand for protein. Making raw milk is not an industry with high barriers to entry so it doesn’t take long for any short term profitability to be ‘normalised’ by new entrants. And remember, New Zealand has no competitive advantage in making raw milk in New Zealand from cows fed on supplements.

The current cycle will no doubt work its way through and the world price of traded raw milk will settle at some level that will dictate again to New Zealand dairy farmers what the most profitable on-farm dairying formula should be – all pastoral, a mix of grass and supplements, low intensity or high intensity – who knows? It will be some combination of all. But with a price of farmland now driven to such giddy heights that the earnings yield from dairying can’t even compete with the already low interest rates available on bank deposits – it is likely the industry is in for a big shudder.

All of which begs the fundamental issues around this industry in New Zealand. From the perspective of national economic interest it is pretty dumb to allow one industry to grow to such a size that it can hold the economy to ransom. It is even dumber to enable that expansion by virtue of an Act of Parliament that prevents that industry from being subjected to the normal market disciplines of capital markets. To frame regulations that ensure capital be pumped into an industry to the extent that it staggers with bloat, where income returns get smaller and smaller as a percentage of assets deployed – is little better than doubling down at the roulette wheel.

I’m not talking about Fonterra actually. The protected sector in dairying is on-farm. The legislation enables the farmers to demand that all but a fraction of the net revenue that Fonterra makes is passed back to the farmer in the price of milk-solids. There is only one way an entrepreneurial farmer can respond to that signal – which is to increase the volume of milk produced.

Back in the 1990’s when the debate over this industry was at its zenith, some of us were pretty persistent in our criticism that such an industry structure would end in tears. The Directors of the then NZ Dairy Board were equally adamant in their rejection of the idea of deregulation, fearing their industry would fall victim to corporate raiders of the Brierley ilk and that would spell the end of the industry. So against the advice of many including the Commerce Commission, the government intervened and the farmers got their way. The rest as they say, is history.

What could the alternative have been? An industry that transitioned toward a situation where movement of capital was free, would have seen less investment on-farm and a lot more downstream. It would in other words, have facilitated investment in the most profitable parts of the supply chain, not eschewed that in the name of keeping 100% ownership of a supply chain that manifestly is super-strong at the on-farm end (that is no longer profitable) and pathetic beyond the farm gate (where good money is still being made from global consumer products, exporting New Zealand’s on-farm technologies and breeding expertise, processing and marketing from dairy ingredients etc).

For sure the industry may have been smaller (although watch this space) but it would have had far more resilient profitability. For the country as a whole it would have avoided the burden of being ‘too big to fail’.

The government may be saying now it is not going to bail out the industry this time around but you’d be brave to bet against it doing exactly that. This political pressure can be seen from Andrew Little’s rather bizarre suggestion that the Government pressure the banks to prevent farmers being forced off the land, land prices falling and farms being bought by foreigners. This is too little, too late – land prices need to fall, and sadly foreign buyers are the only hope we have of prices not falling too far.