For families’ sake it’s time to rethink our welfare and tax systems.

For families’ sake it’s time to rethink our welfare and tax systems.

The Prime Minister’s reaction to the latest survey of child poverty was predictable but misguided. It is not just about jobs. As the welfare regime already attests with its Working for Families regime, earned income for many is lower than they can live on.

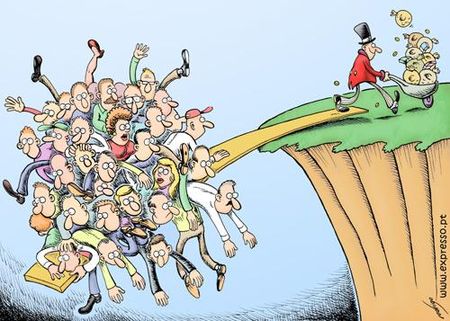

The inadequacy of the crumbs that trickle down to those occupying the increasing number of low paid jobs is a reality of contemporary New Zealand. Having more people in jobs that pay inadequately is hardly the solution.

Let’s not stay in denial. This is a rich society. There is plenty of income to guarantee a dignified life for all. The only relevant question is how to achieve that. When it comes to children the view that the “sons should bear the sins of the fathers”, which accurately sums up the disregard for child poverty, should be an affront to the Kiwi egalitarian value. Living in a country with a sidelined and increasingly angry minority has consequences, as many countries have found to their surprise in recent years.

It is clear too that the ideal of equal opportunity is a million miles away from the New Zealand reality of 2013. The question is, what do we do about it?

We need to be very clear about the problem. What does unequal opportunity for children look like? The evidence is overwhelming that it doesn’t simply mean being raised by parents who have a low income. Yes, having poor parents makes it harder for children to do well at school, but on its own it is not enough to derail them. It doesn’t increase the chance they will end up in prison for example, or become a teen parent. For that to happen, a lot else has to go wrong during their childhood. These other childhood “risk factors” include, but are not limited to, having parents with an addiction problem and experiencing violence at home.

Low parental income can be a catalyst for the other risk factors – being poor brings pressures that using alcohol and drugs, or being violent, may alleviate for a while. But raising income alone will be ineffective if the other risk factors are not addressed, whatever their cause.

The programmes needed to protect high-risk children are pretty well identified and we won’t go into them here. But what is missing in the child poverty debate is the role wider economic policy is playing in destroying the family life of some children. New Zealand’s targeted benefit system, which is delivered by Winz, is often criticised for providing too little income for those who rely on it. The result is that beneficiary families can be socially isolated and at risk of poverty-related poor health. The children are more likely to struggle at school.

But what needs to be said equally is that the targeting doesn’t work and the system as a whole isolates and stigmatises recipients, denying them a sense of agency (that important feeling of being in control), which is indispensable for self-esteem and mental well-being.

The public’s impression is that every beneficiary ends up with the same support. Nothing could be further from the truth – asset testing is minimal, so it is possible to be both wealthy and a beneficiary. Some recipients are well supported by family and friends, a factor which Winz can only imperfectly take into account. Others fail to get support because they cannot make their lives “fit” the ideal profile as defined by Winz. Not only is this grossly unfair but it means some fall through the gaps.

Winz’s support is designed to fit the “perfect” family of two parents caring for their children. But many families, especially those most at risk, are structured differently. Who is caring for the child may vary from week to week, for example. A teenager with living parents but no parental interest or support is another anomaly. Trying to navigate these differences has led to a complex entitlement system that only specialist advocates can understand. Many benefit applicants would miss out on their entitlements if they fronted up to Winz unaccompanied by an advocate.

In myriad ways, then, the system of targeted welfare undermines the mental and physical well-being of beneficiaries and puts their children at added risk. Yet none of this is inevitable. New Zealand can well afford a system of income support which does not finger-point. Paying each adult over 18 an unconditional income each year would support those who have no other source of funding. Importantly it would say that each and every adult is as worthy of respect as any other, and our demonstration of that respect is the income we as a society guarantee. An unconditional system like this would support adults and children across the whole gambit of family structures.

If the welfare system is the elephant in the room when it comes to ruined childhoods, then tax policy is rampaging next door.

Every citizen benefits from public services and should pay. Even beneficiaries pay tax on what they get. Yet there are some types of capital that produce economic benefits for their owners that are not taxed in New Zealand – the most glaring oversight is property.

Perpetuating the loophole on this form of income means not only that the owners are free-loading on the rest of society – abhorrent given the percentage of them who are the country’s richest – but their personal economic standing continues to race further ahead of the pack. By not insisting that every economic benefit produced in New Zealand pays the same amount of tax we are endorsing parasitical behaviour that undermines the social fabric. There is no excuse.

That master chronicler of blighted childhood, Charles Dickens, nailed it when he said: “If the misery of the poor be caused not by the laws of nature, but by our institutions, great is our sin.”

A lot of attention has been focused on tracking the number of children being raised by parents with low incomes and/or suffering illnesses known to be caused by inadequate income. And that is a good thing. It is also an indictment on the government that philanthropists have had to step in to provide the information on this that the public demands. However there is much less attention on the prevalence of children living lives marred by multiple risk factors.

In this regard, a report put out by NZ Stats in 2012 makes interesting reading. These results were based on the General Social Survey (GSS) done in 2010, so are a bit dated. However this is a rich survey, comprehensively quizzing 8,000 adults about life in their household. It doesn’t drill into all of the risk factors identified as important by the public health experts for children in those households but it picks up on the experience of the adults they live with in terms of social isolation, poor mental health, physical health, limited access to facilities and a range of other economic-related indicators (for example, whether they live in overcrowded housing).

Defining children as ‘high risk’ if they experience five or more of 11 risk factors (see details below) Stats NZ reports 6% or 67,000 children are ‘high risk’ and a further 19% or 201,000 are medium risk (3 to 4 risk factors). It’s a no-brainer that the most at-risk kids deserve the most help.

The programmes needed to protect the opportunities of high risk kids are pretty well identified. Trials that involved hands-on mentoring and support for parents whose children were identified as high risk showed good results for example. The benefits of strongly connecting these kids to their community also seem to be widely accepted. What seems to be lacking here is the political will to roll the programmes out with sufficient funding and robust provider monitoring.

The 11 risk factors related to the adult who lived in a household with children.

Was the adult:

1. A current cigarette smoker.

2. Victim of crime in the last 12 months.

3. Living in a high depravation area.

4. Feeling isolated some, most or all of the time.

5. Has poor mental health.

6. Victim of discrimination in the past 12 months.

7. Has a low economic standard of living, based on the ELSI (economic living standard index).

8. More than one housing problem.

9. Living in an overcrowded house.

10. Limited access to facilities.

11. Poor physical health.