We all know the story of the Emperor who has no clothes. Due to a nasty bout of self-importance and misinformation fed to him by those with a clear agenda, His Royal Greatness steps out in public totally starker’s to announce to the enthralled onlookers that he is wearing the finest most expensive garments in the land. Ultimately this approach didn’t turn out quite so well for him once a small child sniggered and pointed out the reality of the situation….

It occurs to us that the tax on sugary drinks argument has striking parallels with this story and is a fable the Government could spend a bit more time reading at bedtime.

Jonathan Coleman and John Key have said again and again they will not be introducing a tax on sugary drinks because there is absolutely no evidence it will work. Jonathan Coleman has been careful lately to add the disclaimer ‘to decrease obesity’. He is adamant about the evidence being clear on its lack of effectiveness. A local policy think tank has gone further and claimed that

“There is just no evidence that a smallish tax on fizzy drinks will reduce the overall sugar intake of those consumers the legislation is meant to protect from themselves”.

Yet confusingly, most public health academics in the country signed an open letter stating that a sugar tax was the best thing we could do to address the obesity crisis in New Zealand. A follow up letter in the Herald by one of them (Professor Rod Jackson), a man never known to mince his words, really put the pedal to the metal and said the government needed to pull finger and implement the tax before we killed more kiwis with the appallingly flimsy excuse of there being ‘no conclusive evidence’ it works.

What is the general public to think when there is such a major (and lets face it kind of bizarre) divergence in views about what the evidence says? We have to look past the bluster and examine the quality of the evidence each party is holding fast to. Because despite someone telling us they are wearing the finest robes in the land the reality is someone here is seriously misinformed and is actually stepping out in cold in the nude.

NEWSFLASH! Not all Evidence is Equal

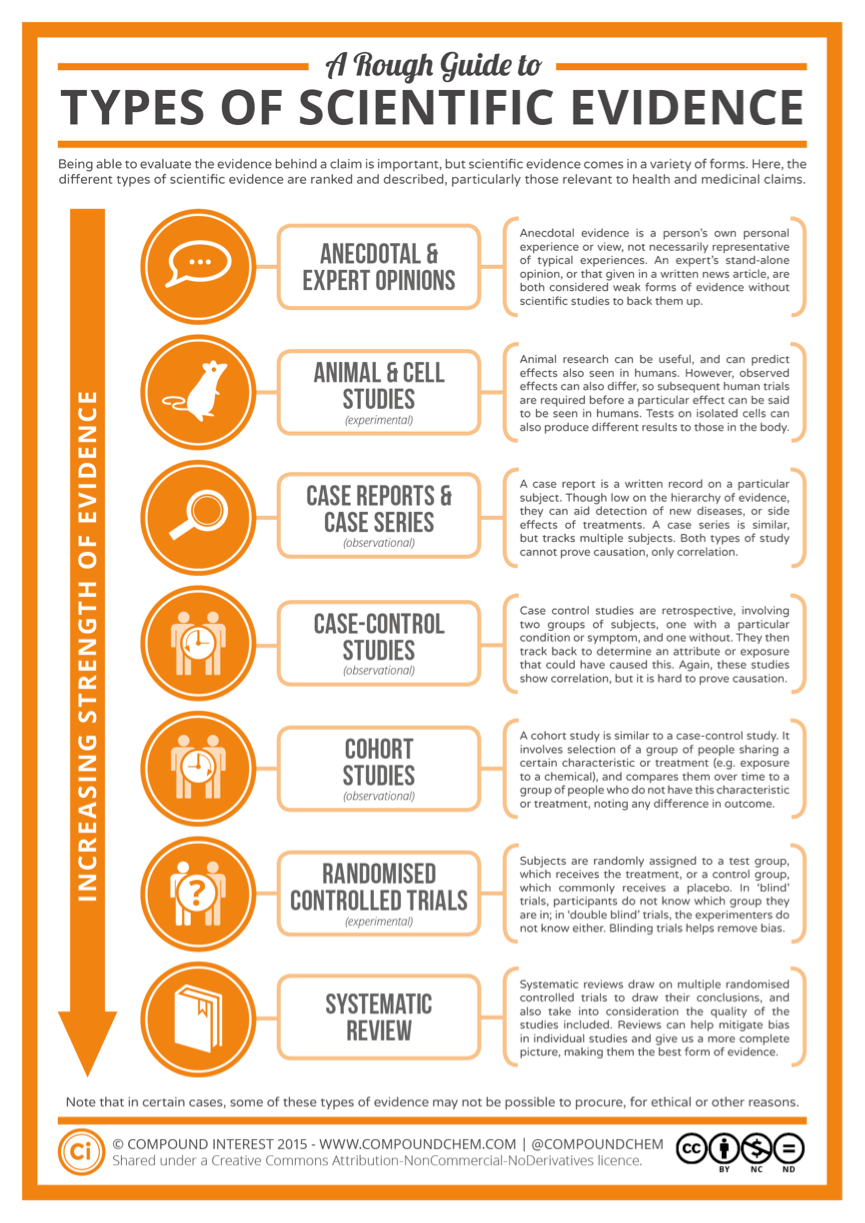

Most of you who have read any of our blogs will probably be familiar with the idea that some evidence is better than other evidence. Anecdote for example is not evidence it is just a story about someone’s Granddad who smoked heaps of fags and died aged 100 when they were hit by a bus- or some other such magical stroke of fate. To get a little more complicated than this there is actually a whole hierarchy of different types of evidence and a systemized approach on how to ask a scientific question, search for the evidence and understand and draw conclusions from it.

Without this approach people in positions of influence using the evidence inconsistently to support their pre-existing position. In the trade we call it ‘confirmatory bias’. We all do it. Everyday in lots of little ways we seek evidence to support how we understand the world. But when it infiltrates the creation of public policy it is not science, it is just a big naked man in our midst claiming to be wearing robes of gold.

Understanding The Hierarchy Of Evidence

So without getting too pointy headed about it all, when we want to know what interventions works best to improve a specific outcome (and we are primarily talking about improving people’s health and well-being in this blog) we look across all the different types of ‘evidence’ produced (in an unbiased way) and try to find that evidence which is strongest and of highest quality. Give or take a few definitions there are around 7 major types of evidence out there. They range from the weakest type of evidence (anecdote and expert opinion) to the strongest (Randomised Control trials and Systematic Reviews). Below is an infographic that describes in detail the hierarchy of evidence.

The main point to take home is that certain study designs are better than others to answer questions about what works, and we need to focus on the best we have available at the highest level.

What happens when one study contradicts another?

As with the sugar tax debate we do get bamboozled with contradictory individual pieces of research – most which seem on the face of it like they are good quality. These days we have what can only be described as an avalanche of scientific information to come to grips with. Sense about Science estimates there are 1.8 million research papers published in scientific journals every year. So along with deciding which types of individual studies we should believe (which the hierarchy can help us with), the next challenge is how to interpret the results of a study in the context of all the other research that has been done? The solution is to take a systematic approach.

Systematising the Search and Analysis of Evidence

The advent of a more evidenced-based approach to practicing medicine brought with it a transparent and replicable process for finding the answer to particular scientific queries. For example, how could we find out what works to reduce obesity in children in developed countries using the best available evidence, while avoiding all the potential individual bias that may slip in?

And so the Systematic Review was born. The main distinguishing features of a Systematic Reviews are highlighted in the box below and for the science nuts details on SRs are included at the end of this blog.

What you need to know about a quality Systematic Review

- It needs to be an ANALYSIS of the evidence not just a literary review of the selected studies.

- The question needs to be very precisely defined so the right studies are swept up and compared with each other.

- All the methods for the searching of evidence, assessing the quality, analysing the results and drawing conclusions must be detailed and replicable.

Read more about Systematic Reviews

The history of tobacco legislation in the UK is a good example of how the use of high quality evidence assessed in a systematic way changed practice and improved health for large group of people. When in 1948 in the UK government statisticians noted a large increase in lung cancer, it was thought that perhaps air pollution was the culprit. Then a study of lung cancer patients in London noted that those who smoked were 50 times more likely to develop lung cancer. So many people smoked in those days it was hard to be sure of the connection, so a larger study was designed. Over 40,000 Doctors were surveyed (smoking was at that point deemed to be beneficial to your health) and in 1954 the association between smoking and lung cancer was confirmed. By 1962 the government issued guidance that smoking caused lung cancer and moves were made to implement policy changes including advertising changes, taxation, and public education.

In summary, the way to know what evidence is the best evidence and what the whole body of evidence tells us is to use this gold standard approach. That is especially true in contentious areas of policy where powerful industry groups stand to lose a lot if certain interventions are implemented – like sugar taxes or climate change. A systematic review really is the golden robes made by the finest tailor in the land.

So Who is Wearing The Golden Robes and Who is Naked in the Sugar Tax Furore?

The signatories to the sugar tax letter cite an evidence review completed by Public Health England. It is the same review that informed a sugar tax in the UK. As with all reviews completed by Public Health England they take a transparent, systematic approach to reviewing the evidence. They have an entire handbook describing their systematic process.

What process Jonathan Coleman (or any other detractors) used to reach his ‘evidence synthesis’ that sugar taxes don’t work is pretty unclear, The same goes for the lobby groups and think tanks that also oppose junk food taxes – the analysis behind their claims is scant.

Coleman has added that the evidence for sugar tax is not ‘definitive’. The thing is in order to support the implementation of his 22 obesity reduction interventions over a sugar tax, he would need to have data showing that his package is more effective at reducing childhood obesity than sugar tax. Not only that but these interventions are definitively effective (i.e. 100% of people responded to the intervention). But again no such evidence has been produced (nor will it ever as Rod Jackson pointed out). On the other hand here is a systematic review telling us that taxing sugary drinks may reduce obesity and there is evidence it could lead to a decrease in BMI, and that is even before the most recent evidence from Mexico‘s new policy to tax sugary drinks was published.

We will leave it up to you to decide who is naked in public here ….

The Process of Systematic Reviews – For the Boffins

In a high quality systematic review those asking the question must go through a number of fundamental replicable steps. The first step involves asking the research question in a very specific way which defines what people (for example children), what intervention of interest (for example taxes on sugar), what comparison intervention (so for example health education) and the outcomes of interest (for example consumption of sugar, weight plateau, weight loss). Sometimes we add a timeframe into it (for example over 10 years). The question is then framed for children, does sugar tax compared to health education campaigns reduce consumption of sugar, stabilise BMI or reduce BMI over a ten year timeframe?

The importance of this question is paramount because it is the first place where bias can creep into evidence reviews. If for example we simply ask does a sugar tax work, things start to go very pear shaped. Work on what? Work compared to what? Work for who? After how long?

After the question there are then a number of other steps to a quality Systematic Review:

- A systematic replicable search (using something called a search strategy) for all the published (and sometimes unpublished evidence)

- A transparent and systematised approach to excluding research that does not meet the inclusion criteria (which has been pre set)

- A transparent and systematised approach to identifying and rating the risk of weaknesses and strengths of each included study

- A transparent and systematised approach to analysing and combining the study findings meaningfully (sometimes this can be done statistically if the studies are not massively different from each other). The reviewers will then make a statement about the answer to the question that was asked.