Every group needs an equal say — granting unique power to anyone is a quick path to a divided nation.

Big changes are being discussed over the way political power is shared, changes that should make all Kiwis sit up and take notice.

There is definitely a conversation to be had about Maori aspirations, but the Waitangi Tribunal is not the place to be having it.

In recent weeks the Waitangi Tribunal found that Ngapuhi and other Far North tribes did not intend to cede sovereignty when they signed the Treaty of Waitangi. If taken to its logical extreme, this means that Maori who signed the Maori version of the Treaty didn’t hand over the reins of sovereignty to the Crown.

This finding contradicts not only earlier tribunal findings but also the reality that sovereignty does lie with the Crown – after all it’s the Crown Maori have been negotiating with and which taxes New Zealanders to pay settlements.

Meanwhile, a debate is stirring over Maori representation on local councils. The New Plymouth Mayor, Andrew Judd, already embroiled in a debate over whether his council should have a Maori ward, is calling for all councils to have Maori provide half of their councils. This, he believes, would better “reflect” the Treaty of Waitangi. Demonstrating if nothing else, just how dynamic interpretations of the Treaty have become, the Judd model seriously undermines democracy in New Zealand.

Maori have aspirations, and achieving those should as far as possible be supported by other New Zealanders. These aspirations include having more say over their own lives, and eradication of socio-economic disadvantage.

But is the best way to achieve those aspirations to grant Maori unique political power over matters that affect everyone? That is a question all New Zealanders need to wake up to and discuss.

[quote pull=”right”]Maori have legitimate grievances, even once the so-called settlement process is completed.[/quote]To accommodate degradation of democracy is risky in the extreme. It also contravenes Article Three of the Treaty, which in 21st-century terms holds that we are equal citizens – one person, one vote. More worryingly, political theory and experience points out that granting unique political power to any group is a quick path to a divided nation.

Despite what many people believe, the Treaty is not a legal document, and the tribunal is only an advisory body (with the exception of recommendations on State Owned Enterprise land).

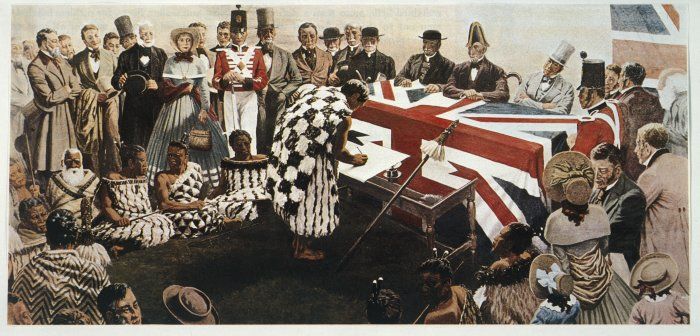

When it comes to issues of political power, the tensions within the Treaty, and between the Maori and English versions, mean that neither the Treaty nor the tribunal can help us much in choosing the best way forward. There is no mileage wondering what someone meant when they signed the Treaty in 1840.

Beyond the specific carve-outs around natural resources and cultural treasures of Article 2, when it comes to making decisions that affect everyone, we should all have a say, an equal say. This is fundamental to democracy.

So while recent agreements like the Whanganui River settlement are completely appropriate, the decision by successive governments to retain the Maori seats under MMP look out of place, as the Commission on Electoral Reform concluded. And to the extent that local councils deal with issues beyond natural resources and taonga – like bus fares – the Judd proposition is nuts.

Maori have legitimate grievances, even once the so-called settlement process is completed. However, there are other ways of achieving Maori aspirations without granting unique, and potentially divisive, political powers. We can explore more devolution, which could allow all communities more say over how things are done without compromising political equality. We need a new approach – one that looks at all the options and listens to all citizens. Confining the discussion within the purview of the Treaty industry is just dangerous.

The tribunal, using the Treaty as a guide, has done a good job in resolving historic grievances. But looking to the future of the relationship between “Group Maori” and the bulk of society, we need to widen the discussion to ensure the public is well aware of the consequences of some of the proposals coming through.

Sadly, many non-Maori are uninformed on the Treaty and particularly its modern interpretation. This renders the public vulnerable to some seriously misguided and offensive proposals emanating from the Treaty industry, and gives no lasting solutions to Maori aspirations. It’s a lose, lose.

[box]NEW BOOK: Are We there yet? – The future of the Treaty of Waitangi

Three questions: ‘Where have we got to with the Treaty of Waitangi?’; “Is where we have got to a good place?’ and ‘Where do we go from here?’ This book is a record of what we discovered as we tried to answer these – what we thought at the time were simple – questions. But nothing is simple when you start asking questions about the Treaty of Waitangi! Two years later we have emerged battered and bruised but with something we want to say. ‘Fellas, we might be about to crash the truck and you’re not even looking!”

What we’ve ended up with, and what we present here, is a personal assessment of the way New Zealand is governed and, in particular, of the changes that have been happening to peoples’ political rights over the past few years. Changes that have been introduced in response to pressure to honour the Treaty of Waitangi. That means this book is ultimately about New Zealand’s constitution but don’t be put off by that word. This stuff matters and we could do a whole lot better than we are.

Click here to enter your email below to get updates, articles and promotions relating to the book.

[/box]