In our last blog we looked at whether the claims of ‘rock star’ economist Thomas Piketty held any water or not. Short answer is that some did, some didn’t. In this blog we turn to what we should do about his insights.

The purpose of taxes, benefits and the government provision of services is (at least partly) to redistribute income. We don’t pursue equality as that would crush any incentive to get out the bed in the morning to create wealth, however there’s a general social contract that our economy should be fair. As a result, we champion equality of opportunity, so that everyone has the resources they need to get started, and has the incentive to work hard, to work smart. A fine balance is required and there’s plenty of room for argument over the detail here.

Piketty’s charge is that inherited wealth will beat hard graft every time, which doesn’t sound like a good thing if protecting equality of opportunity is the aim. However by taxing wealth out of existence the solution he suggests pretty much roasts the goose that lays the golden egg. We suggest that the Comprehensive Capital Income Tax (CCIT) put forward in the Big Kahuna is actually the Goldilocks ‘just right’ middle ground that addresses the unnecessary causes of the polarisation Piketty admonishes capitalism for.

We’ll start by looking at the standard responses – progressive income taxes and a capital gains tax – and why they don’t cut the mustard.

Raising the top tax rate & Capital Gains Tax aren’t the answer

Piketty has suggested a return to Muldoon-type tax rates – up to 80% for the top income earners. The trouble is that this approach doesn’t work; it is complicated, and the wealthiest people don’t pay the top rate of income tax anyway.

A Capital Gains Tax is no better – especially with an exemption on the ‘family home’ – more loopholes for the wealthy to exploit to their advantage. Capital gains taxes are complicated to administer, are an unreliable source of revenue (some years they would lose the government money), and even if they were imposed efficiently, it’s highly likely whether taxing capital gains is taxing the symptom rather than addressing the problem. We do not agree with capital gains taxes.

In short, the Labour/Greens proposals to raise the top tax rates and introduce a tax on capital gains were pretty much just symbolic, they wouldn’t have solved the problem.

Piketty’s answer – taxing wealth

Piketty is on the right track here – the tax on the effective income people reap from their wealth is nowhere near as complete as the tax on income earned by labour. The problem with capitalism, he points out, is that we don’t tax capital (or better said, the effective income from capital) enough.

However, Piketty goes too far. Depending on the size of the fortune, Piketty suggests taxing wealth itself using tax rates of 0.5%-10% per year. This would be on top of any income tax paid on the income produced by the wealth (such as interest from bank accounts). Piketty’s proposal could cut a massive swathe through a fortune over time. In doing this he is trying to bring the returns to capital down to the same level as increases in other income like wages, so the owners of wealth don’t grow richer.

There are a couple of problems with taxes on wealth of the magnitude Piketty prescribes. Any country trying to do this would see its capital owners flock overseas. You’ll never get a global agreement because it would always be in the interests of some country to offer up a tax haven.

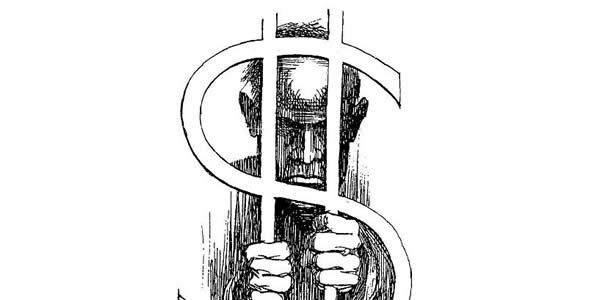

But the most serious flaw with Piketty’s proposal is that it removes the very heart of a capitalist economy. Why would anyone bother to work hard and accumulate wealth if they were taxed on it to the extent that they couldn’t grow richer? It’s just silly to remove the incentive to get rich, it lies at the heart of capitalism.

A comprehensive capital income tax avoids these problems

There is an alternative that addresses the core of the inequity and inefficiency in capital’s role in our economy. We proposed it in the Big Kahuna: Turning Tax and Welfare on its Head.

The income from assets that are returning cash income, like bank accounts and shares, are already fully taxed and shouldn’t be taxed again. Piketty has gone too far in suggesting this. But what about assets that aren’t returning cash returns? They are still providing a return to their owners, otherwise they wouldn’t invest in them. So why do we not tax these returns too?

Here is an example – owner-occupied housing. If you didn’t own your own house you’d have rent someone else’s – and they would pay tax on that rent. That’s a clue to the size of the rewards owners get from their houses – it’s equal to the tax implicit in the rent they would otherwise have to pay.

A second example is businesses people run simply as tax shelters. They claim all the depreciation on the assets they deploy to make no profit – at least no profit after the wages they’ve paid themselves. Farmers are into this like robber’s dogs but so are many other self-employed. It is nothing but a tax loophole. Utilising the business assets for personal use is almost a national sport for the self-employed. It is a tax rort.

Our insistence on selectively exempting the non-cash income a capital asset can endow its owner is of significant consequence. This tax loophole is worth about $6bn, and the wealthy and middle class Kiwis that own their own homes are all cashing in. It alone – let alone the ease of leveraging this type of investment via mortgage finance – explains our obsession with investing in housing, and the investment bubble we have as a result.

A comprehensive capital income tax – which applies the tax rate to a deemed risk free return that capital could be applied to – would tax zero or minimal profit-making businesses on the income they’re enjoying from the assets they deploy, and would tax owner-occupied housing as if owners were paying themselves rent. It would put the biggest part of our national wealth – housing and land – on a par with all other assets and firmly within the tax net. It would have the added bonus of popping the investment bubble in property and placing it on a level playing field with investment in other types of capital – factories and software for instance. And it would rid us of pseudo businesses that are nothing but a tax dodge – something the FBT has failed to achieve.

A comprehensive capital income tax doesn’t fall prey to the same problems as Piketty’s proposal. There is no double taxation going on. In many ways this is just a proper income tax – taxing all the benefits owners get or could get from their assets, not just the cash income they may or may not earn. In essence there is a minimum tax that all owners of capital must pay – whether via income tax or the CCIT on the value of the capital. Such closure of the tax base for capital would bring much effective income within the gambit of the tax base for the first time. The major change would be that for the first time we’d be taxing at least part of the true returns to housing and land.

[box type=”alert”]Want to know more about this CCIT? Watch this Whiteboard Friday video[/box]

Got my house, boat, bach – I’m alright Jack

People will whinge at the thought of a new tax, as the concept of taxing our housing or land is an anathema to most Kiwis. It’s important to understand it’s not a new tax, it is merely income tax properly and comprehensively applied – quite different to the current income tax regime that hits PAYE payers properly but nobody else. By defining the tax base properly we could also remove the progressivity in the income tax regime, which is another source of gaming the tax regime. In fact our view is a flat rate of income tax is critical on every dollar earned. As we suggested in the Big Kahuna, the revenue raised from this tax could help fund an Unconditional Basic Income of $200 per adult per week. The triple of a CCIT, a UBI and a flat rate of income tax is the meaningful reform of our tax and welfare regime required for the system to be fair and efficient.

If we are serious about reducing inequality of opportunity and giving everyone a fair go, as well as getting the most efficient deployment of our capital resources then we have to move away from this idea of accumulating assets and then sheltering them from the tax man. Have you ever wondered why the Coromandel Peninsula is full of multi million dollar homes that are unoccupied most of the year? Now you know – property is the most tax efficient place for the rich to stash their cash.

More and more this Kiwi dream of home ownership is becoming the preserve of a privileged few, and the national pastime of accumulating housing is severely distorting our economy. Worse of all the distortion drives the problems that Piketty has raised. If we want to tax wealth as Piketty suggests, then a Comprehensive Capital Income Tax is the best place to start.

Want more on all this stuff?

Listen to Susan Guthrie from the Morgan Foundation discuss Piketty’s thesis in the New Zealand context with Kathryn Ryan on Nine to Noon – Radio National

The Piketty Phenomenon – New Zealand Perspectives (being released today)

Collected in this BWB Text are responses to this phenomenon from a diverse range of New Zealand economists and commentators. These voices speak independently to the relevance of Piketty’s conclusions. Is New Zealand faced with a one-way future of rising inequality? Does redistribution need to focus more on wealth, rather than just income? Was the post-war Great Convergence merely an aberration and is our society doomed to regress into a new Gilded Age?

Capital in the 21st Century – Thomas Picketty

What are the grand dynamics that drive the accumulation and distribution of capital? Questions about the long-term evolution of inequality, the concentration of wealth, and the prospects for economic growth lie at the heart of political economy. But satisfactory answers have been hard to find for lack of adequate data and clear guiding theories.