Local democracy is failing to deliver in many parts of the country, which in some extreme cases (Canterbury) has led to the removal of their powers. In Auckland a similar threat hung over the Council if they didn’t pass the Unitary Plan. Is this the right response or should we be giving them more powers instead to make them more relevant.

Falling Turnout

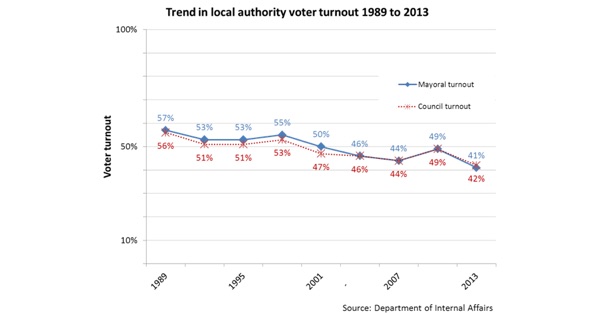

Local democracy is locked in a vicious cycle, which ultimately looks like a death spiral. Turnout at its elections has dropped precipitously from almost 60% in 1989 to almost 40% in 2013. Compare that with national elections with 77% turnout, down from around 90% in the 1940s and 50s.

Falling voter turnout is a problem in many countries at all levels of government, but in our local authorities it is getting to the point where democracy is seriously compromised. The result of poor turnout is that decisions are made in the interests of a shrinking group of voters; usually the older, wealthier members of society. This of course reinforces existing divisions, making people even less likely to engage in the whole process.

We’ve seen a number of examples of this in action: Auckland Council’s repeated bowing to the NIMBYs that oppose increased density of development in inner city suburbs; the capture of Horizons Regional Council by farming interests in order to water down the plans to improve water quality; the frustration Environment Minister Nick Smith has publicly expressed over lack of progress by Regional Councils on water quality, despite 95% of Kiwis saying they want swimmable rivers.

What can we do?

Low turnout suggests that local authorities are failing to work in the best interests of the population. Does that mean we should get rid of them or limit their powers further? That seems to be the Government’s ultimate response, but it may only make the problems worse – further undermining local government and thereby ensuring declining engagement. Are there other options?

Of course, making it easier to vote would help. Given the decline in post boxes online voting is long overdue, but was stymied this time around. However, much like compulsory voting, reducing the barrier to vote doesn’t mean that people will make better decisions.

The fundamental problem is that many people simply don’t see the point in investing the time in understanding local politics enough to make an informed decision. This is known as salience – a feeling that your vote will not make a difference.[1] Voting in local elections, as it stands, simply doesn’t make enough of a difference to the lives of the voters for them to warrant taking an interest.

In New Zealand, spending by local authorities is 3.8% of GDP and 11% of total government spending. Contrast this with the UK where local authority spending is 10% of GDP, and 26% of total government spending. That sort of spending power is worth people getting out of bed and voting for, because it funds stuff that affects their lives.

So maybe instead of stifling local authority spending in order to improve their effectiveness, we should be increasing it. There are plenty of examples of areas where our central government has given local authorities responsibility for an issue but left them without any of the effective tools to deal with it.

Giving local authorities more power

Perhaps the best example of this is transport. Auckland Council has been talking about congestion charging for years as a way to pay for transport infrastructure, but Government has only recently seen the light. Meanwhile in Wellington most mayoral candidates are making promises that they can’t keep because roads are outside their jurisdiction. Central Government determines the spine of the road infrastructure (State Highway 1), and can even ignore whether projects meet a cost benefit test. Then the local authorities have to scramble around making public & active transport fit those decisions by central government.

On the environmental side, Local Government New Zealand is also calling for the tools their members need to deliver their responsibilities. They want the ability to levy taxes and royalties (e.g. for water use and pollution) and to compel developers to contribute to environmental projects to offset any damage they do.

The New Zealand Initiative has argued that local authorities should be able to experiment more with policies in Special Economic Zones. They also argue that local authorities should be able to keep some of the financial benefits from projects such as housing developments and mines as an incentive to overcome NIMBYs and encourage economic activity locally. These ideas are promising, provided they are balanced with environmental and social needs to ensure true progress.

The trouble is that no politician is going to hand more money and power to local government when they are in such a democratically parlous state. It is a catch 22. In the next blog we will look at some more practical short-term solutions to the malaise.

New Models of Local Democracy

Local democracy is in a death spiral. Turnout is low, partly because they have no power. They have no power (and no immediate prospect of getting more) because performance is poor. Performance is poor in part because turnout is low.

How do we break the cycle? The “go to” in our culture is amalgamation; such as Auckland’s super city model. That approach is a sensible way to deliver regional services – water and roads for one – but falls down for others. Auckland is still struggling to manage that balance with its Local Boards, and other regions such as Wellington have rejected that solution outright.

And why should it work? If people are struggling to engage with local body politics when it is local, why will they engage more when it is at the more distant regional level? Remember a key determinant of election turnout is that people think their vote will make a difference to their lives. The only advantage of absorbing local government into regional government would come if central government devolved more responsibility to them.

Another option would be to reduce the power of the Council generally and invest more power in the Mayor – the London model. That might get people more interested in finding about that contest at least. The Auckland reform went some way towards that model but elsewhere the mayoralty remains a pretty toothless position.

So how can we break the death spiral and restore the confidence of both the people and central government in local government? There are answers, but they involve persuading politicians to hand over power, which can be difficult.

Over the past few decades, new models of democracy have emerged. In the old days governments and councils provided information or, if you were lucky, consultation. Now we have found ways to involve citizens, collaborate and even empower them to make the decisions. These new approaches have huge potential, provided the politicians are content to remove themselves entirely from the decision making process.

Collaboration can be powerful but has a checkered history in its short time in New Zealand. The best example is the Land and Water Forum, which has had some limited success but not as much as it should have. The main problem is that it isn’t true collaboration, because Government is involved in the forum but then picks and chooses what it will implement. This approach lacks credibility, which is why Fish and Game have walked from the process. If you are going to all the bother of collaborating and compromising to find a position that everyone can agree to, you don’t want to then have someone else making the final call.

We are now seeing collaboration being used for Wellington transport. After the Basin Flyover got kicked for touch, NZTA swallowed its pride and sat down with the local authorities to hammer out a long-term solution in a process known as Get Welly Moving. This is promising, but it remains to be seen how truly open to ideas they are. At the moment NZTA is spending billions funneling more cars into Wellington’s CBD; a place where many people are expressly demanding better public transport, walking and cycling options to enhance denser inner city living.

We can go even further than collaboration by empowering local communities to make decisions themselves. Citizen’s assemblies and juries are where a representative group of citizens come together to debate and make a decision. Experiments have shown that when ordinary citizens are armed with the evidence they make incredibly rational decisions.

We are seeing this approach used to resolve the Island Bay cycleway dispute. After a great deal of controversy the Council has gone back to the community to find a solution, including helping them develop a 10 year plan for the development of the suburb. Mayoral hopeful Nick Leggett wants to give this same opportunity to other communities.

The added bonus of this approach is that it is very much aligned with our Treaty obligations. The Maori version of the Article 2 of the Treaty includes the word rangatiratanga, which in the English version was incorrectly defined as property rights. In modern terms it really is the right of communities to have a say in how their services are run. To honour the Treaty we have to offer this opportunity to Maori communities, but there is no reason all communities couldn’t take it up. Rangatiratanga could be for everyone.

Low turnout, and the resulting poor performance of local authorities is a real concern. But that doesn’t necessarily mean we should push more power to the centre; quite the contrary. It could be a sign that we need to do local democracy differently.

[1] Mark N. Franklin. “Electoral Participation.” in Controversies in Voting Behavior p. 87