This week Canterbury Community Law published some research on what it was like to be a beneficiary in the Canterbury region. While the research was not representative of all beneficiaries’ experiences in New Zealand, it does highlights the dehumanising, belittling, confidence sapping, and stigmatising experience that being on welfare can be. It makes for grim reading.

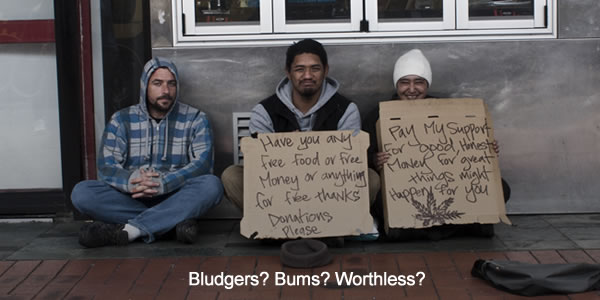

The response was predictable, in the columns of Stuff and on talk back radio the entrenched view that those on a benefit are worth less than the rest of us reared its ugly head. Do beneficiaries really deserve to be treated as worthless? What impact does this attitude have?

Beneficiary bashing has become a national sport

Perhaps however it is time to find some better sport elsewhere.

Those beneficiaries who participated in the Canterbury research frequently noted the ‘power imbalance’ present in their dealings with WINZ staff, they talked of humiliation, distress and a lack of privacy. The need to explain their personal circumstances and their need for help – which they already felt embarrassed by – to a new person every time they attend an office. All which contributed to what the authors noted is “the perception that the benefit system was dehumanising”.

These were perceptions confirmed by both those advocating for beneficiaries and those who worked in the system.

A community advocate noted “it’s where you get your money from”. …You can feel the punitive or the kind of authoritarian [approach]… you can see people just kind of cowering, just kind of going into themselves.”

A Work and Income case manager said “If I was looking at it from a beneficiary’s point of view, I think that it must be really aggravating. Because you already probably feel quite powerless as a beneficiary because your financial security’s decided by powers … And then you kind of have [the] face of your case manager, but it’s a different case manager every time, so it’s kind of just like a faceless power that’s deciding how much money you have and don’t have. And then you have your long wait time. I mean, it’s not a very welcoming environment”.

Is this a Representative Experience though?

International research has shown that for many people being on welfare is a deeply distressing experience in itself.

Research carried out on behalf of Ministry of Social Development (MSD) found “In a study of UK lone parents… almost one-quarter felt that life’s problems were too much for them and one-half felt, at times, that they were useless. Almost one-fifth felt that they were failures”

This is hardly surprising as international research has shown that many developed societies (like the US and NZ) tend to see welfare recipients as lazy and unmotivated. This leads to a distinct stigma attached to being on welfare. Further research has shown those who find themselves in need of welfare internalise this stigma (they see themselves as failures and worthless). In addition when welfare programmes are delivered in negative, punitive, and power based ways those feelings of worthlessness and low self-esteem increase.

This is exactly the experiences that those from the Christchurch study describe “one person described being made to feel like a “bludging lowlife bum”, and another beneficiary as a “second class citizen that deserves nothing”.

Does stigma give people the motivation to get off benefits quicker?

Ironically this is exactly what DOES NOT work to get people off benefits. When you feel bad about yourself and your life circumstances, it makes it pretty hard for most people to get motivated to upskill, to take risks, to look for and take employment on when the opportunity arises. When someone else behaves in a way that confirms those feelings of stigma it makes the problem even worse.

On the other hand, there is good evidence that a positive experience when receiving welfare, a supportive and encouraging attitude from case workers and agencies is key to successfully moving off welfare- especially for those on it long term.

Being treated well empowers most people to get off a benefit

Various welfare to work schemes in the UK – many focussed on single women parents – have found that having a positive relationship between beneficiaries and care workers is critical to finding work. Ironically, this research has been summarised in work commissioned by The Ministry of Social Development.

Solo parents who took part in a scheme in the UK called the Personal Adviser scheme, identified the boost in confidence that their Personal Adviser gave them as a major factor in their success. Another UK based scheme aimed at moving lone parents into employment, noted that “the most successful approaches worked by boosting confidence and motivation and broadening horizons. Confidence building coupled with social support were key elements.”

And so it goes on “information, encouragement and support provided by case managers were identified by participants as the most important elements in helping their transition into employment”[1]

The same work commissioned by the Ministry of Social Development clearly identified the role of low self-esteem, and low confidence in preventing the long term unemployed getting into work.

Of course this is a simplistic view of the issues at hand, there are many parts to the puzzle when getting people into work. However, treating those who are on welfare positively and as though they deserving of support is a good start.

A Unconditional Basic Income would address all these issues

Of course a UBI is the ultimate multipurpose solution to the beneficiary bashing that goes on, the sense of failure that people, who need a benefit, can feel, and the treatment they receive at the hands of those that administer such a system.

In the meantime, while we are stuck with a costly, inefficient and stigmatising system, beneficiary bashing seems to be shooting ourselves in the foot.

The Morgan Foundation is doing some research. We would like your help

[polldaddy poll=8879538] [polldaddy poll=8879541] [polldaddy poll=8879549]

[1] Evans, H. (2000) Sprouting seeds: Outcomes from a community-based employment programme, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion Report No. 7, London School of Economics, London.