The Government has committed New Zealand to a climate change target for 2030. Once you look behind the headline numbers, the target is grossly underwhelming, which calls into question whether the Government is really serious about the existing target of reducing net emissions by 2050 to 50% of the 1990 gross emission baseline[1]. Or have we officially abandoned that commitment now, a commitment gazette under the Climate Change Response Act?

Not only that, but the previously announced target of a 5% reduction from 1990 levels by 2020 looks set to be achieved through pretty questionable means. Minister Groser just seems miles away from the calls being made by the international science community for action to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees. His seems to be a strategy of deceit and shifty sliding of baselines: smartarse gaming of the rules maybe, but ethically repugnant.

What do the numbers mean?

The Government has promised a 30% reduction in emissions by 2030. Sounds great, right? Until you realize this target is from the new and higher baseline of 2005 gross emissions levels, rather than 1990 gross emissions as we have used in the past. The 2005 baseline is much higher than the 1990 baseline – 27% higher to be exact. A higher starting point means we have to do less to achieve the goal. A 30% target from the 2005 baseline is the same as an 11% target from the 1990 baseline. Sounds pathetic when put like that.

The Government argues that the 2005 baseline is used by some of our major trading partners, such as the United States. However, the 1990 base was used in the Kyoto Protocol, and has become the standard particularly among European countries. As a comparison, the EU as a group has set a target of a 40% reduction in emissions by 2030, again using 1990 as a base.

All New Zealand’s previous targets are also expressed using the 1990 base year. They include a 5% reduction by 2020 and a 50% reduction by 2050 (complete with the catchy tagline of “50 by 50”).

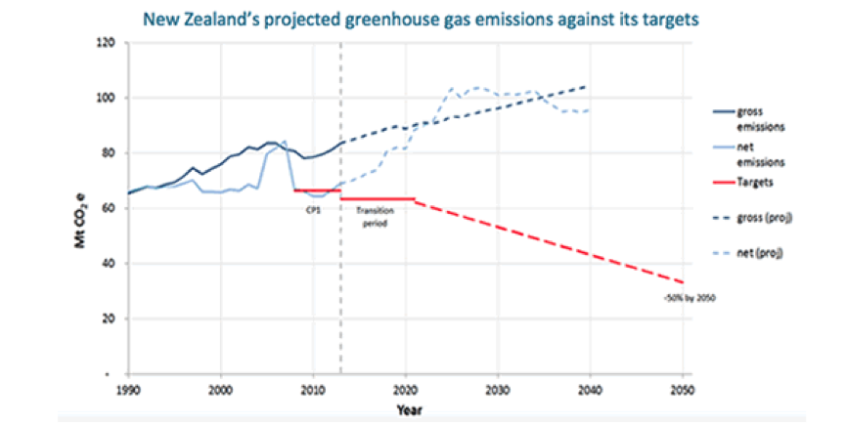

The reason for switching the baseline is obvious from the chart below – New Zealand has made zero progress on reducing emissions since 1990, so setting our starting point later means that we don’t get punished for that inaction. If we put this target in terms of reductions from the 1990 baseline, then it equates to an 11% reduction by 2030. We’re playing games – a reality unrelated to the “ambitious” targeting the Minister claims. Further, it delays the remaining 39% reduction to the 2030 to 2050 period – assuming we are still committed in any way to deliver on that earlier commitment to reduce emissions by 50% by 2050, from the 1990 base. So following on from no action since 1990, the government of New Zealand is now pushing the hard work out another 15 years at least. Anyone smell a rat?

The Government is also being deliberately vague on the land-use accounting rules that apply to the 2030 target. This allows them wriggle room to argue for looser rules around the treatment of forestry during the negotiations. Most other governments have been far more transparent about the rules they intend to use. While the Government may have a point here (and would do on the treatment of methane also, but it doesn’t seem to be pursuing that), it doesn’t help our negotiating position to have a weak target and a lack of clarity on the rules.

The “Consultation”

The Government’s consultation document (we say Government because it is difficult to believe it was written by competent officials) made it clear that they were not expecting to put forward an ambitious target. Nevertheless, people engaged in the process in good faith. Out of 15,000 written submissions, 99% of people argued for a more ambitious target than the Government chose. Not great news for democracy – the Government is really confirming it is out of step on this one – something that’s been obvious ever since Groser started his shifty dilutions of our commitments back in 2013.

How will we achieve the 2030 target?

As we have seen in previous blogs, our emissions continue to rise despite committing to various reduction targets. On current projections, our gross emissions are predicted to be more than a third above 1990 levels by 2030 – net emissions could be even higher depending on what happens to forestry. On this trend meeting any target looks unlikely. Our government is nothing but a blowhard on climate change – all talk and gestures while doing the opposite.

The most imminent deadline is the 2020 target of a 5% reduction from 1990 levels. The Government appears to be remarkably sanguine on this target, despite our growing emissions. A peek at the Emissions Trading Scheme data quickly tells us why. New Zealand companies have been buying up shonky overseas carbon credits over the past few years while prices have been at bargain basement levels. For example, credits under the ‘Clean Development Mechanism’ have collapsed from €14/t in 2011 to less than €0.5/t since 2012.

These credits really make a mockery of the international carbon market – so much so that Europe has severely curtailed their use. Not us though – we plan on presenting these credits in 2020 as proof that we are doing our bit on climate change. It’s all a bit sick – the kind of cynical response to climate change you would expect from a baby boomer politicians who don’t give a stuff about future generations.

This reliance on trading our way out of trouble creates two concerns. Firstly it is not sustainable – while the price of carbon has been low recently it is unlikely to stay that way. The longer we rely on buying and put off doing anything, the more expensive change will become when we finally have no wriggle room left to buy cheap credits. Secondly there is a well-established principle in international negotiations of ‘subsidiarity’. The idea is that countries can use trading, but this should be only a small part, of the overall strategy. At the moment, trading is our strategy. – we have no other legs to it. Another part of Groser’s cynical gaming.

So what should our target be?

We have already written extensively on this. In short, the focus for our Government should be on carbon dioxide emissions rather than methane, and we should be calling for a review of the way forestry is treated. Those points aside, there is plenty New Zealand could be doing to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. These are currently still on the rise in New Zealand, and must urgently be brought under control as we need to gradually wean ourselves off fossil fuels this century. Any plan should keep that ultimate goal in mind and work backwards from there.

The real question is once we have a target, what do we need to do to make progress? Regardless of the target the Government needs a plan to deliver, which it currently doesn’t have. Rather it delights in shifting baselines, target dates, sticking with discredited international trade in credits. The Groser approach is to game the regime to irrelevancy.

We will share more ideas on what meaningful actions New Zealand could take in an upcoming blog. Don’t expect this government to give a damn about that though.

[1] ‘Gross’ emissions exclude the carbon dioxide soaked up by forestry, ‘net’ emissions include it. It may sound weird to have a target that compares net with gross, and it is, but that is pretty standard in international negotiations.