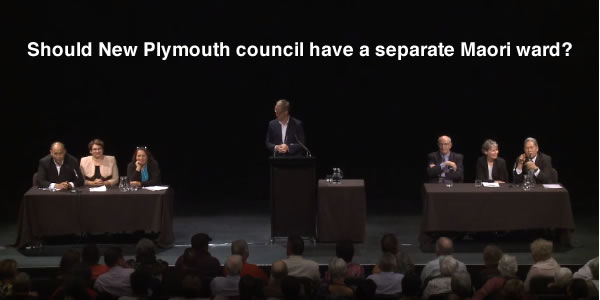

Last night Morgan Foundation researcher Susan Guthrie took part in a public forum on whether New Plymouth should have a separate Maori electoral ward. Around 400 people turned up to watch Susan, Winston Peters, Willie Jackson, Marama Fox, Hugh Johnson, and Metiria Turei debate the issues.

Susan’s speech and the recording of the debate below, and you can watch it online here. Susan’s message was that any move away from political equality puts the fabric of society at risk, so we shouldn’t do it. But nor should we stick with the status quo: we need to invest in communities having a greater say in the delivery of services that affect their lives. That is a more challenging approach but also far more rewarding.

If you don’t want to watch the video you can read my summary notes here.

Susan and Gareth have spent the past two years researching and writing a book on the future of the Treaty of Waitangi. “Are we There Yet: the Future of the Treaty of Waitangi” will be available in bookstores January in time for the 175th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty. You can stay up to date with the book release here.

Susan’s Speech

I would like to begin by thanking the Mayor and the council for this wonderful opportunity to have an open and honest debate about their recent decision to create a Maori ward. It means we can all talk about New Zealand’s constitution. That’s a conversation which is long overdue. It’s a refreshing step up from what the government has done. The 2013 Constitutional Review for example was a complete waste of time.

The rules behind New Plymouth’s local elections are ultimately part of New Zealand’s constitution. Our constitution changes all the time, whenever we make a new decision like this. That makes NZ very unusual in the world.

This flexibility provides freedom to fine tune and improve, but it has a downside. We make constitutional decisions incrementally, one at a time, typically operating in silos

You can back yourself into a corner will many small, poorly thought out steps, and I would argue that is exactly what has happened in NZ over the past decade or so.

We’ve been making small, incremental partially-informed constitutional decisions one at a time and we’ve backed ourselves into a corner. The Local Electoral Act 2001 was one of those steps. New Plymouth council’s decision to take advantage of the provisions in that Act to create a Maori ward, while well-intentioned, is another.

The constitutional changes that we’ve had, and the demands that are being made for more, have been couched in the name of the Treaty of Waitangi. This emphasis upon the Treaty has made the debate dangerously narrow.

I don’t disagree that the Treaty is hugely important for New Zealand. It’s a founding document that provides great inspiration for the ongoing relationship between Maori and the rest of New Zealand society. The Treaty has been enormously successful in bringing about the long-overdue recognition and settlement of historic Maori grievances arising from colonisation. It has overseen the very welcome renaissance of Maori culture. The Treaty settlements provide a strong economic base for Maori going forward.

However, too much is being asked of the Treaty beyond this. The Treaty does not lend itself to a constitutional debate.

I’m not saying don’t have constitutional debates, in fact I’m saying we must have them. What I’m saying is don’t try and force that debate through a Treaty framework.

Take the Maori ward for example. If it is combined with geographically-defined wards, it will give Maori more influence than others over all the decisions the council makes. That gives Maori unique political rights, it is a move away from democracy.

Maori voters who opt to be included in the Maori ward will have a direct voice on the council, unlike other minorities such as Pasifika and the disabled, for example.

Everybody other than Maori will have to take their luck with the neighbours, hoping they can persuade them to share their views and vote the same way.

Voting at large, as you do for the Mayor, is consistent with political equality. Voting with electorates defined the same way can do it. But having different electorates defined in different ways is a problem.

In my view it is impossible to show convincingly that the Treaty supports Maori aspirations to have unique political rights, that New Zealand should move away from democracy.

To do so demands too much of history. It requires establishing what the signatories understood in 1840 about the concept of ‘state’ and the role of government. That’s problematic enough. Then there is the job of extrapolating that understanding into the 21st century. But that’s not the only problem.

The Treaty’s Article 3 spelt out that there would be equal citizenship in New Zealand which has a clear meaning in the 21st Century – political equality, democracy.

If the Treaty can’t credibly provide clear guidance on the constitution, it won’t lead to consensus. And you need consensus for any reforms to be enduring.

But the bad news doesn’t end there. By looking through the lens of the Treaty and nothing else we have ignored a great deal of information that is relevant for constitutional design.

We need a new framework to think about our constitutional decisions. One that is evidence-based, forward looking and risk- focused.

In other words, we should start looking at constitutional design as the rest of the world does. There’s a whole body of international knowledge and experience we can draw on. But it’s never talked about here.

To begin with, we need to step aside from loud demands for unique political rights and look at hard evidence about representation. Let’s try to be objective.

Is it true that Maori are not effectively represented in elected bodies like Parliament or the council? This is more subtle than asking whether a Maori candidate is elected, it means asking whether the elected body continually comes up with decisions, or is likely to, across the full spectrum of its responsibilities, that Maori support.

You can shed light on this using empirical evidence. How different are Maori values and aspirations from those of non-Maori across the wide range of council activities. If they’re similar, its likely geographically-defined wards will provide effective representative government for Maori. Another piece of information we could use: how satisfied are Maori with council decisions?

A quick scan of some of New Plymouth council’s results suggests satisfaction might be quite high. While Maori make up 15% of the population here fewer than 5% of survey respondents with a view say they are dissatisfied with what the council does when it comes to parks and recreation, waste services, water and libraries for example. This suggests the majority of Maori in New Plymouth agree with many council decisions. In other words, it looks like they may well be effectively represented.

There may be specific issues where Maori disagree with the council every time, and they need addressing, I’ll come to that shortly. But across a wide spectrum of council activity, on the face of it representation doesn’t seem too bad.

Quite apart from the evidence on representation, we might still be inclined to give Maori unique political rights. We might want to make sure there is always a voice directly representing Maori on the council. And that would be achieved by the Maori ward. But there are significant risks with this. These risks aren’t discussed in NZ but they are well known overseas.

While there are bitter disagreements internationally when it comes to constitutional design, one thing everyone seems to agree on is that it’s a bad idea to create unique political rights for groups that are defined by something fixed and arbitrary like descent or ancestry.

If you do that, you create incentives for leaders of these groups to exaggerate existing differences between their group and the rest of society, and to create artificial differences. Social difference becomes something which is deliberately cultivated because there are political rewards attached to it.

You create dynamic forces that force your population to see themselves as something apart from one another, to choose one side – Maori or not Maori – when in fact they may see eye to eye on a lot of issues. That’s a significant problem, but not the only one.

By tying unique political rights to descent you risk stepping on the rights of people within the protected group. We’ve already seen that in NZ where iwi tend to be the focus of engagement between central government and Maori leaving urban, not iwi-affiliated, Maori out in the cold.

You might be asking “Who cares if the decisions we make about the electoral wards create social divisions we wouldn’t otherwise have had?” I would say you’d be mad not to care.

The overseas evidence on this is compelling: countries with strong social connections among their population – especially across communities that differ by ethnicity or religion – have the greatest social and economic success. They provide the best opportunities for their children, they have the best outcomes from education, the best outcomes in health, people feel safe, suicide rates are lower, fewer people are in prison.

The key to succeeding on these measures is social connectedness, neighbourliness, trust. The opposite of social division. Social connectedness is an asset that is produced in our communities – not in Parliament, not in our councils – although they can destroy it – it is built in our workplaces, our schools, our malls, on our streets.

Social connectedness doesn’t mean assimilation – it doesn’t mean that by becoming better connected we all become the same. It means that we trust one another and value each other’s differences.

If we choose rules which create unique political rights for Maori – like special electoral wards – we risk eroding our social connectedness over time.

It’s not this generation we have to worry about, but the next one. The constitutional decisions we make today can create divisions that get worse and worse over time. That’s the key insight the international literature offers us. NZ has a lot of social connectedness compared to the rest of the world. But we can lose that so easily.

If not the Maori ward, then what? Status quo? No, I would say New Plymouth Council could do a great deal that would be positive for Maori while not eroding the political rights of anybody else. I would encourage the council to look hard at how it might devolve some of its decisions to local communities, as an alternative to creating the Maori ward.

Giving some council authority to communities would introduce flexibility in how specific issues which are of concern to Maori are addressed. It would also be a step towards meeting the Maori aspiration to greater community autonomy.

And working together on specific community policies, would create new opportunities for Maori and non-Maori to reconnect. That would go a long way to building the enduring trust and respect between Maori and non-Maori, the social capital that will ultimately drive the future we leave our children.

Already around NZ you can see this approach playing out – in Canterbury and the Wairarapa freshwater management has been handed over to local committees for example with iwi, schools, farmers, businesses and towns people all working together to protect and restore local waterways.

Sure, it isn’t always easy when communities of Maori and non-Maori come together to work on local issues. But if the people involved live locally they have that in common. If they have real authority, there is an incentive to work together – the power they have is real, not token.

So my message is this: decisions that take us away from political equality put at risk social connectedness which is the key driver of the social and economic opportunities we create for our children.

Don’t do it. But don’t stick with the status quo either: invest in greater community autonomy, empower your local communities and foster social connectedness. And accept nothing less than everyone – Maori and non-Maori – standing tall in every world they occupy, don’t force them to choose just one.

Yes, that is a tough agenda, and I would say far tougher than creating a Maori ward, but we shouldn’t let that put us off. We have a responsibility to step up and do the hard yards needed to build a decent constitution for the generations to come. And one of those first important steps is being taken in New Plymouth.

Broadcast live streaming video on Ustream