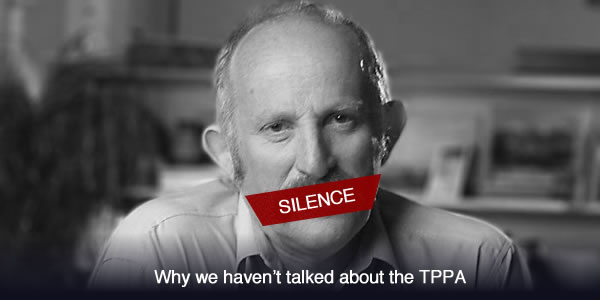

The Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPPA) is probably the most talked about economic issue of the year, apart from our age-old favourite – housing. Today the TPPA will even be the focus of protest marches around the country. As many of you have pointed out, we at the Morgan Foundation have been uncharacteristically silent on the issue. It is not like us to not have an opinion!

The trouble with the TPPA is that we don’t really know any of the detail, so it is actually impossible to make an informed comment. This lack of information is concerning, and might be reason enough for the protest marches. Generally free trade is a good thing, but if the worst-case scenario is realised then the TPPA may not be in our best interest.

What is the TPPA?

So what is the TPPA? It is a proposed regional regulatory and investment agreement with twelve participating countries: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam. According to the partner countries the TPP is intended to “enhance trade and investment among the TPP partner countries, to promote innovation, economic growth and development, and to support the creation and retention of jobs.”

Free Trade is generally good

The basic rule of economics is that when two people trade, they are both better off, otherwise why would they trade at all? This basic rule applies right up to the country level. Why not let people trade with as many people as they can? People can get what they want more cheaply than they could before, which means they have more money to spend on other things, which means they are better off.

We have seen this play out on a global scale since 1820 as countries have increased international trade. According to the OECD, trade has grown the incomes of the poorest countries on the planet, particularly in the last fifty years. In other words, be wary of the anti-trade luddites that want to cut New Zealand off from the world.

But there are winners and losers

While trade makes us all better off collectively, it is not be all sweetness and light. Some people lose their job in the process, as we have seen in most of the Western world with manufacturing jobs moving to China and Vietnam. While people can usually find another job, it may not necessarily pay as much, particularly for people with fewer skills. As a result the less skilled workers of the western world have seen several decades where their pay packet has been growing slowly, if at all.

How do we total up these different impacts? We all benefit from cheaper goods, skilled people can take advantage of a more productive economy to procure higher incomes, and the Chinese benefit from the extra jobs that come their way. The world is certainly better off overall, but not everyone is sharing in the gains. This is one of the causes of the current discussion on inequality.

New Zealand has a lot to gain and few jobs to lose

New Zealand is quite unique in that we have a lot to gain and not a lot to lose from free trade – mainly because we opened up most of our markets to trade long ago. So regardless of the trade deal we are unlikely to lose many jobs. On the other hand if barriers to entry are reduced or eliminated then we have a lot to potentially gain by selling a lot more produce – dairy, meat, wood – into other countries. At first blush, any free trade deal sounds like a good idea. Any doubter need look no further than the NZ China deal, which single-handedly may have sheltered us from the global financial crisis.

For those TPPA opponents who have watched a lot of videos from overseas, such as the United States, it is worth bearing this in mind. Most of the objectors overseas are from the industries that will lose out. For example the less efficient farmers in the United States fear more efficient Kiwi farmers coming in to steal their market share. So be careful whose propaganda you swallow on social media.

But the devil is in the detail

The trouble is that not all free trade deals are created equal. Nor for that matter are they all that free. Any deal involves a fair swag of horses being traded, with each country trying to make sure they are better off. The result is a horrible complicated mess – actual free trade would be a lot simpler.

Even where there is a free trade deal, some countries play silly buggers, as the Aussies did for so long with us over apples. They make up reasons why we can’t sell certain things in their country – in the case of apples it was fireblight. Most free trade deals nowadays include rules to try to stop these sorts of shenanigans.

And there are no details for the public to see

The trouble with anyone wanting to comment on the TPPA is that there is no detail to discuss. No facts. Not really. Just assurances from our Ministers that they have our best interests at heart when they sit at the negotiating table.

On one hand, this is understandable; after all how can Tim Groser negotiate on behalf of New Zealand if he has to run back and check everything with 4.2m people? On the other hand, the process is gravely lacking in transparency. Surely there is a better way of doing things.

What are the main concerns?

At the moment we are reliant on Wiki Leaks and rumour to understand what might be in the deal. Given that New Zealand is unlikely to lose out large in the jobs stake, there are two major concerns remaining: our government getting sued by companies, and Pharmac getting neutered. Both of these seem to impact on the health sector first and foremost, which is why doctors have come out expressing concern on the TPPA.

- Losing Pharmac’s super powers

We commented on this issue when it first arose back in 2011. The bottom line is that the TPPA should leave Pharmac alone – it ensures we get the best value from our limited health budget. It does this by negotiating a tough deal with international drug companies, and only investing in drugs that give the best bang for buck. The fact is that Big Pharma simply doesn’t like someone using their own hardline negotiating tactics against them.

If the problem is that Pharmac is too frugal and we don’t spend enough on drugs, then Pharmac’s budget could be increased. Given two decades of constrained spending on drugs while the rest of the health sector spends willy nilly, it may well be time to spend more on pharmaceuticals. But we should leave the system the same – which means leaving it up to Pharmac how to spend that extra money. They will ensure that New Zealanders get the maximum health benefit from those extra dollars.

- Getting sued by foreign companies

Leaked documents from the ongoing negotiations show that on the table is a proposal called the ‘Investor-State Dispute’ procedures. Basically this proposal could amount to giving any foreign investor the right to sue our government, in oversees tribunals with no right of appeal, for implementing any policy or legislation that hurts their financial interests.

These provisions have been brought into trade agreements in recent years to deal with shonky third world governments whose corrupt decisions can send a business under. That is probably fair enough, although you might equally argue that we need an international court to take care of the international businesses that are also shonky and corrupt.

However, these provisions take on a whole new light when they are applied in the first world. We have a stable democracy, and a healthy balance of power between Parliament, the Beehive and the courts. Why do we need international scrutiny of our democratic decisions? The rule of law applies and should be enough. Any business that gets regulated probably deserves it.

The main concern here is that this provision would stop our government being able to legislate for the public good if that hurts an international business interest.

[box]Example: Plain Packaging of Cigarettes

The best example at the moment is plain packaging of cigarettes – Australia is getting sued by Philip Morris (a tobacco company) for trying this tactic to reduce smoking. This is happening under Investor-State Dispute procedures that are part of Australia’s trade deal with Hong Kong, and could apply more broadly under the TPPA. They are also being challenged by Cuba under existing trade rules (the World Trade Organisation) because their precious cigar industry has taken a hit.

Plain packaging has worked across the ditch – those drab olive ciggie packs with pictures of diseased eyeballs does stop people buying as many cigs and is particularly off putting for young smokers. But before we follow suit and implement the policy, the New Zealand Government is waiting for the outcome of these cases. Presumably they have one eye on signing the TPPA.

You can see that there is a threat to democracy here if under the TPPA a multinational can prevent a country pursuing policies it deems are in the public interest. Scary. In our view we need to wait and see the outcome of this case before we sign the TPPA, to understand exactly how far this right to sue extends.

[/box]

Summary

In summary, we remain in a wait and see mode on the TPPA. There are a lot of gains to be had from removing barriers to international trade, but when that infringes on a government’s ability to adopt policies that protect and enhance the social well-being of its people, then falling to our knees at the altar of free trade becomes a ritual too far.