One of the tenets of classical economics is that markets are rational (in other words, logical), that in the end if enough people participate, the outcome will be optimal. This assumption is often criticised and is why governments intervene via regulation and corrective taxes when they decide the market isn’t working. In reality, we often see markets misfire, with concentration of power leading to people being ripped off by the powerful.

Still, the basic presumption underlying capitalist economies remains that “more often than not” the market knows best, that the outcome it delivers is “mostly” better than one a paternalistic government might engineer.

So for this economist it’s always fascinating to test the theory, to see when a crowd gathers and is delivered full information, whether it does come to a rational decision or whether instead even the law of large numbers is no guarantee that the market will act sensibly. The recent phenomenon of crowd-funding provides many opportunities to test the madness of crowds, to see whether indeed when people gather in large numbers, their collective action is rational or rather – more often they stampede hysterically and deliver outcomes they didn’t intend.

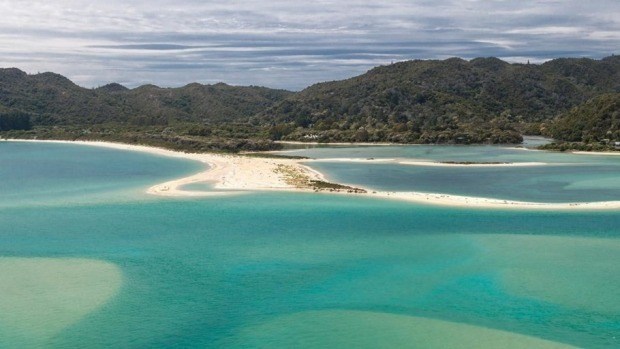

The crowd that has gathered to buy the Awaroa sandspit provides just such an opportunity. There is no doubt the common objective – to save access to the beach for the public – is the primal call, to which the donors, their agents, the popular Press, politicians – have all cheered along. A couple of coordinators have conducted the exercise and very early on they determined (most probably from a discussion with the vendor’s Real Estate Agent) that $2m should buy the property.

$2m is well beyond the conservation value of that strip of beach, but if it is roughly the market value then clearly it’s driven by another demand – most probably from the financial elite who value the isolation and pristine nature of the location, and even excluding the riff-raff (mainly foreign backpackers). There is some evidence for that, the property was sold for $1.9m, eight years ago.

Anyway the crowd funding began. I was approached for help a week or so later when the funds raised from the crowd at that time were around $1m. I immediately determined this crowd had entered a dogfight with the mega-rich for the property. Also I could see that the glaring weakness of the crowd’s strategy was that it was telling the world how much it was going to bid. It seemed to me the most efficient way to help the crowd get what it wanted was to negotiate outside the tender process the vendor was running – and immediately. To do that you needed to negotiate with them for a “Buy Now” price with which you could secure the deal. Obviously a non-disclosure agreement would be needed so that the tender still proceeded. Real Estate agents do this all the time – two tracking is a legitimate way to engage the market.

So I offered to underwite whatever such a negotiated price might be – or in other words make up the difference. But importantly I would need the crowd to keep growing its contribution otherwise the shortfall I’d be making up would be more than it would need to be. Remember I was being asked to help here, I wasn’t just a member of the crowd who fell in love with the pictures and felt I should contribute whatever to secure the property. Actually I thought the way they’d gone about it was silly and they’d played right into the vendor’s hands. Anyway it was about launching a rescue for this crowd – if it turned out that it would need it.

If I’d just said there and then that I’d make up the difference, the crowd would have stopped donating immediately. I needed a mechanism whereby the crowd would keep donating – perhaps at an even faster rate, since donations were starting to flag. Hence I came up with the idea that I’d demand in return for my help, access to the sheds on the properties. Now remember these sheds will be demolished as soon as the crowd donates the property to DOC – so in effect the crowd would actually lose nothing by giving me the exclusive access to them – it would still have access to the beach and virtually all of the rest of the property. My faith in the animal spirits of crowds told me however that this would make them hopping mad and they’d keep donating to spite me.

The theory is that crowds are rational, and that’s what these sort of experiments test, whether that is a given or whether the evidence suggests “animal spirits” can actually be dominant. In this case would having their nose out of joint because somebody else might be benefitting – even though it’s at no cost to their own benefit – deter the crowd from accepting guaranteed beach access via contract with the vendor? Would it rather take a chance in the tender?

The only objective of my intervention was to secure ongoing public access to the beach – at as small cost to me as possible. I don’t want the sheds at all really – but I did need the public to keep donating so the cost of my underwrite would be minimised. And I was relying on animal spirits for that.

The only failure in executing the plan was that I couldn’t get the promoters to see the importance of entering negotiation with the vendor to get the “Buy Now” price that we needed. The lads were so intoxicated with the magnitude of the crowd’s response and public interest, that they lost – if they ever really had it – sight of the commercial reality of how to secure the property with certainty – to get out of the lottery. Getting that “Buy Now” price was vital. At that stage it could well have been secured at less than $2m even.

Anyway my offer was rejected and they stuck with the ‘promote and hope’ strategy of enticing the crowd in. At least the campaign coordinators have taken my advice and removed the total raised from the internet once the total passed $2m. Sadly now John Key has hopped on the gravy train, showing he is no better than Andrew Little by offering up the possibility of public money to get the bid across the line. It may well end up that the public wins the tender and that would be marvellous – but let’s hope they do it without public money. But then the mega-rich – for whom 1,2, 3, or 4 million dollars is loose change really – may swamp their bid just to secure the property as a plaything for a few years.

So from an academic perspective it’s been an interesting experiment. It does support the thesis that crowds don’t necessarily self-correct to become rational (on price), that animal spirits (emotion) are a significant and persistent factor in markets.

There’s another perspective on this to be gleaned from the current inequality debate as well – and that’s the finding that people would rather go without themselves (lose the tender) than see someone else benefit more than them. This is a common result – illustrated well by the famous monkey experiment where two monekys were quite happy each eating cucumber as a reward for doing a trick, until one started being given grapes. Seeing this, the other monkey immediately refused to eat cucumber (indeed threw it away).

The point of that exercise was to ask the question whether the reason inequality causes so much concern was because the less well-off were harmed, or simply because they were upset that others were doing better. Both the monkey that would rather go without any food than not get grapes, and the crowd who would rather lose the tender than see me get something they didn’t (even though it could cost me an arm and a leg and they can’t get it anyway) – would suggest animal spirits (jealousy) rules.

We all know of the child that would break their favourite toy rather than share it.

Fingers crossed the crowd wins the tender tomorrow.