Over-investment in housing and the lending largesse that underpinned that orgy of excess led to the sub-prime crisis in the US in 2007 which in turn led to widespread recession in the developed world, a problem which remains for most countries today.

New Zealand fared relatively well in one sense through all this – output contracted and unemployment went up, but not the extent it did in other countries. However because of our success, unlike other countries, we failed to shake the excess out of our house prices. Partly prompted by the devastating damage caused by the earthquake in Christchurch, house prices haven’t fallen by much in New Zealand and, if recent new loan approvals are anything to go on, debt-funded investors are at it again.

The RBNZ is worried, saying last week that “housing pressures are an increasing risk to the financial system.” They say their concerns are shared by the IMF and the OECD. The Reserve Bank has responded by penalising banks for providing loans that are high relative to the borrowers equity – a useful measure but powerless against wealthy, equity-rich investors looking to own more than one property.

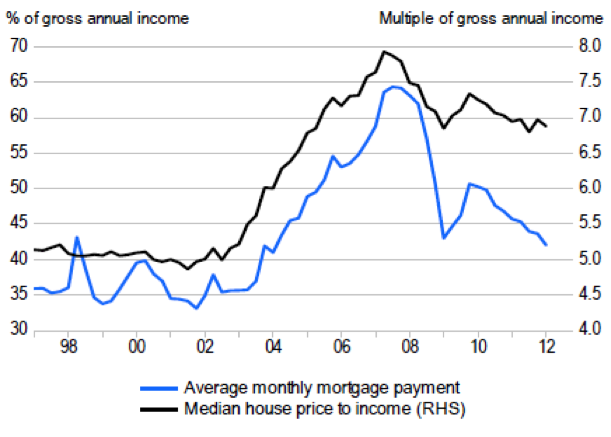

The risks are there for all to see. Median house prices are far higher relative to median incomes than they have been for decades. A Treasury report from July last year spells it out (see the chart). Borrowers are surviving because average monthly mortgage payments are relatively modest, and that’s because interest rates are low. When, not if, interest rates increase this illusion that housing is ‘affordable’ will burst. There is no magic formula to boosting income – especially when the rest of the world is in recession – so that means only one thing – house prices will adjust. It’s an adjustment the rest of the world has had, and is overdue in New Zealand.

House prices and debt servicing relative to gross annual income

The over-investment in housing in New Zealand has been sponsored by irresponsible tax and monetary policies and it has come at a high price: diversion of capital away from deployment in industry and income and employment generation.

The policy failings have historically been twofold:

* Turning a blind eye in tax policy to the benefits owners get from housing. While rental properties and farm are taxed as a business, the capital gains they receive are not considered taxable income. Equally important, the rental equivalent of the shelter provided to owner occupiers and the capital gains they receive are not taxed either.

* A directive to banks from our Reserve Bank to favour lending on mortgage to other forms of lending – this is effected by the lower risk weightings it deems residential mortgages deserve compared to other lending types. The Reserve Bank is tweeking around the edges with this policy – through their higher capital requirements for low equity loans – but it’s not going to get very far without support from a radical rethink on taxing housing.

But the disease remains the same; we have discriminated against productive investment in favour of property speculation. That has intensified the morbid dependency on commodity sales to sustain our incomes. If those hadn’t risen we would be another Spain already.

Why would you continue to gamble on being a one-trick pony? We have an opportunity as the economy picks itself up this time, to remove the policies that discriminate in favour of housing speculation. Why wouldn’t we do that and bring affordability within reach of many more families, like it used to be?

Or should I go out and buy another three houses now and just wait for the rest of you to bid the prices up?