For decades New Zealanders have listened to influential lawyers and political leaders talking about a ‘Treaty partnership’ between Maori and the rest of society (or the ‘Crown’). Significant changes to the way we govern ourselves as a country have been introduced in the name of the Treaty partnership. The Independent Maori Statutory Board (IMSB) set up to advise Auckland Council is just one example.

However, using the Treaty partnership framework to justify reforms like the introduction of the IMSB must come to an end. It is disingenuous and ultimately damaging. Let’s explain.

The courts and the court-like Waitangi Tribunal have been given the task of interpreting the Treaty of Waitangi. That wasn’t too difficult when it came to natural resources and Maori cultural treasures. The wording in Article 2 of the Treaty was clear enough – these resources were to remain in Maori hands unless willingly sold or gifted. Maori grievances over subsequent land losses were justified and stark. Honouring this aspect of the Treaty was long overdue and has been a major achievement of the past three decades.

The Treaty settlements that have been reached over natural resources quite rightly deliver something resembling a ‘compromised private property’ right to Maori tribes (iwi). A lot of land in New Zealand is in government hands but iwi have unique rights over the management and use of it. In the settlement negotiations iwi have conceded full ownership rights over much that the Treaty intended them to keep. Maori are entitled to maintain a relationship with those resources whenever possible.

As we will explain shortly, Maori aspirations are not confined to having tribal authority over natural resources and cultural treasures restored. And it’s here the Treaty offers no guide because beyond natural resources and cultural treasures the wording in the Treaty is vague and self-contradicting. Because of this the courts and the Tribunal decided in the 1980s to overlook the exact wording in the Treaty and instead, steered society (as represented by their elected government) to accept that the Treaty created a partnership between it and Maori. In the name of partnership many changes have been introduced to the way New Zealand is governed (we’ve cited one example above).

There has been no specific definition of the Treaty partnership. It is a moving feast. As issues crop up Maori groups and the relevant arm of government negotiate and come up with an agreement on who must do what. The negotiations could be with Parliament (as commonly represented by the Cabinet), the Treaty Settlements Office, another government department or local government. This incremental, ad hoc process has led us to where we are today – in a dead-end alley with no consensus on the way forward.

The glaring contradiction is that the power-sharing arrangements that we’ve arrived at (beyond natural resources and cultural treasures) are in direct conflict with the wording of the Treaty. Article 3 of the Treaty clearly stated that everyone in New Zealand – Maori and non-Maori – would be equal citizens. On any reasonable interpretation equal citizenship means equal opportunities to influence decisions that affect everyone – political equality in other words.

Power sharing arrangements, which reserve opportunities for Maori to influence public policies that affect Maori and non-Maori alike, breach the ideal of political equality. So while it was convenient for the courts to turn their back on the exact wording in the Treaty, it is disingenuous to ignore it completely and start inventing what perhaps the Treaty might mean in a modern context. The intent of the signatories on this issue of political equality was clear.

There has been no widespread public outrage against recent erosions of political equality yet, probably because the job of applying the Treaty has been given to lawyers (either the courts or the Waitangi Tribunal). This has created the public perception that the Treaty is a legal document, something set in stone that must be followed. But the Treaty is no more and no less than a powerful political agreement. A quick read of Articles 2 and 3 in the Treaty shows that it always was about the allocation of resources and power, which is the bread and butter of politics. And it is clear from the way the Treaty is considered today – interpreted as a relationship and reflected in negotiations between Maori groups and the political institutions of society – that it is a political agreement playing out on a day-to-day basis.

Since it is a political document the job of defining it belongs to the public, not the lawyers. The public has choices to make about the relationship between Maori and the wider society, but it is in ignorance of this, having been all but locked out by the revisionism that the courts and Tribunal have deployed. Using the Treaty to justify power-sharing arrangements in areas beyond natural resources and cultural treasures is both wrong because too often it contradicts Article 3, and is disingenuous because it relies on the public’s ignorance of the true status of the Treaty as a political document.

Justifying power-sharing arrangements by referring to the Treaty is damaging on many levels. It is not building a true consensus because it is based on the public’s ignorance of the status of the Treaty as a political agreement. It is undermining respect for the Treaty among those who are familiar with Article 3’s terms and we can expect this to spread in time to the wider society, risking a backlash. But even more than this, using the Treaty partnership framework has led us to governing arrangements that do not seem ideal for Maori and non-Maori alike.

Like other indigenous people around the world, many Maori aspire for their community to be self-determining. That doesn’t mean they aspire to create a new country, but within this one they seek as a group to be in charge of their own lives as much as possible. Indigenous groups typically aspire to being free to design their own processes and institutions. These might pool resources and distribute them across projects that serve their people such as health and education for example. When not given effective opportunities to do this it is not surprising that indigenous groups resort to the option of lobbying for reserved positions within the institutions of the wider society, such as co-governance roles or advisory boards.

In New Zealand, this last option has been the only one available to Maori (with the exception of the devolution of the management of schools to communities). New measures like the IMSB are more of the same. While not the subject of this article, other options for meeting self-determination aspirations are available. These range from devolution across a wide range of government services, to pan-tribal representative parliaments (the Scottish Parliament is a recent example) to self-determining autonomous regions. What all of these options have in common is an ability to provide self-determination to indigenous people without undermining the ideal of political equality in the wider society of which indigenous people are also members.

New Zealanders are being led to believe they have only one option – a combination of MMP, the Maori seats and positions reserved for Maori within, or with influence over, governing bodies like Auckland Council for example. The Waitangi Tribunal’s Wai 262 report recommended increasing the effectiveness of the positions that have been created and implied Maori should have more reserved positions “..in the very centre of public life.. ‘.[i]

We believe this direction will suit no one and will ultimately generate more, not less, disharmony between Maori and non-Maori. There are better alternatives available. However New Zealand’s obsession with the Treaty has obscured them.

Going forward, New Zealand needs a new framework for thinking about the relationship between Maori and the wider society. The Treaty partnership framework has had its day. Approaching the relationship as ‘group-rights’ issue – as is evident in other countries – has the potential to not only successfully and sustainably address Maori self-determining aspirations but successfully address the pressures arising from New Zealand’s growing multiculturalism too. The potential benefits of a change in mindset are too great to ignore.

[box type=”info” size=”large” style=”rounded”]Upcoming project – In their new book Gareth Morgan and Susan Guthrie assess the modern day interpretation of the Treaty and where it’s sending policy. Their key question is whether the Treaty – now the settlement process is drawing to end – remains the best way to think about progress for Maori and other New Zealanders. Learn more and get updates about the new book [/box]

[i] Waitangi Tribunal (2011). ‘Ko Aotearoa Tenei Te Taumata Tuarua’. Volume 1, p.xxiv.

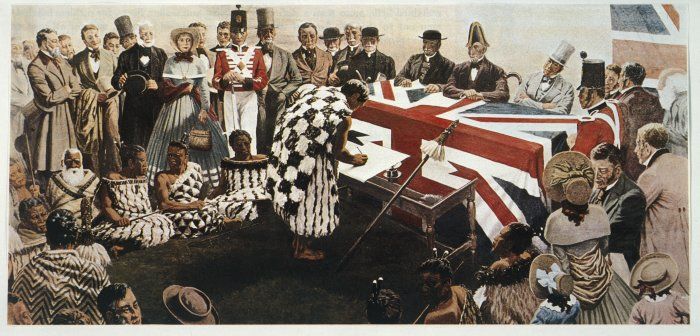

Image from National Library – http://mp.natlib.govt.nz/detail/?id=74674&l=en