As New Zealand’s debt nears half a trillion dollars, people are increasingly asking whether we are at risk of a collapse. A large chunk of that – over $200b – is mortgage debt, fuelled by a housing market boom, the most recent leg of which began in Auckland and is rapidly spreading nationwide. We certainly have a bubble (as we’ll see below), the only question is whether it will burst or simply slowly deflate.

Why are we in this situation? A big reason is the loopholes that exist in the taxation of housing. Based on overseas evidence a capital gains tax won’t fix that, particularly if it doesn’t include the family home as the Green Party has proposed. Our proposal of a Comprehensive Capital Income Tax would close those loopholes, and ensure that our investment dollar gets put in the productive economy where it can create jobs, profit and give us more money to spend on health and education.

As we have explored in the past, another major reason behind the bubble is the favourable conditions given by the Reserve Bank to mortgage lending. As the bubble continues to inflate the Reserve Bank are slowly withdrawing those favourable conditions.

Is it a bubble?

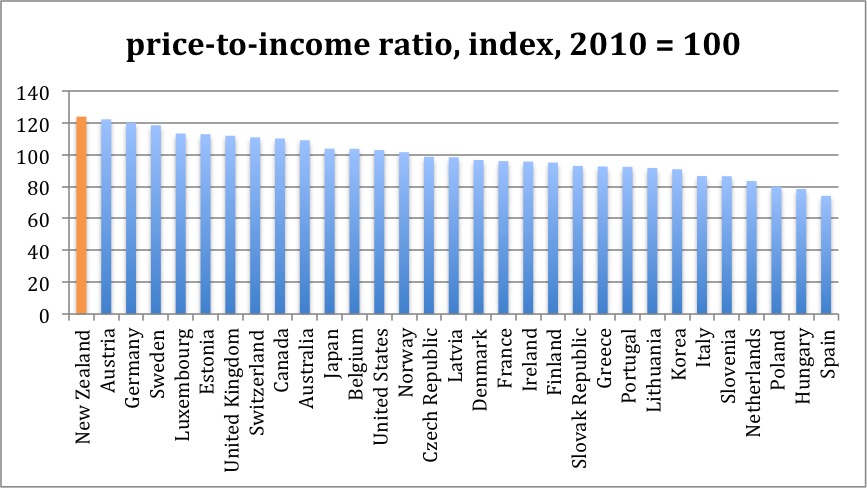

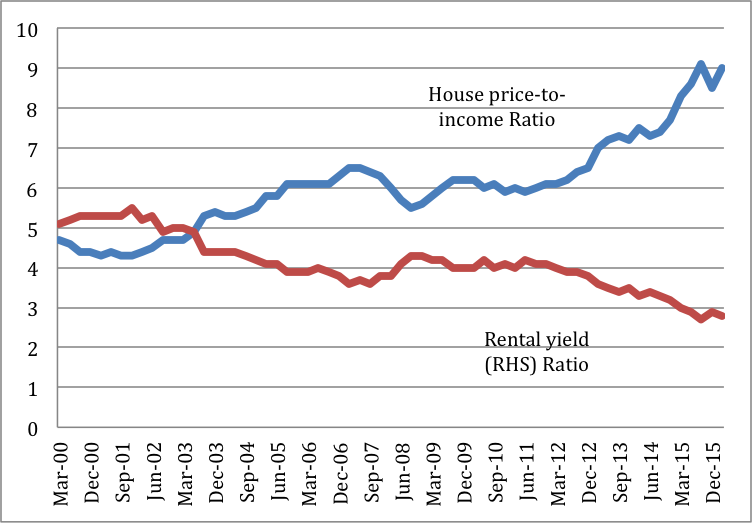

We all know the situation; since 2010 New Zealand’s house prices have risen faster than anywhere in the developed world. In fact, across most of the developed world house prices have been falling in the wake of the global financial crisis.

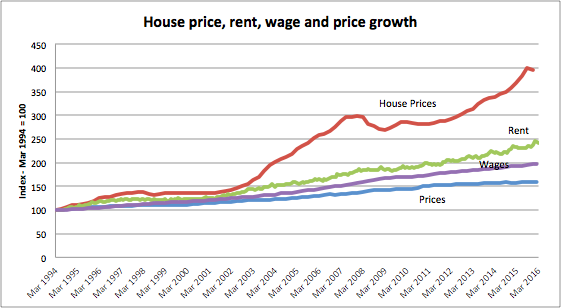

But our problems go back further than that. Generally speaking, house prices have risen faster than rents, wages and prices since 1994. House prices did take a downward blip between 2008 and 2012, proving that house prices can fall, particularly in real terms – i.e. when you consider inflation. Rents have also been rising faster than wages and prices, so housing is getting more expensive overall.

Is our economy at risk?

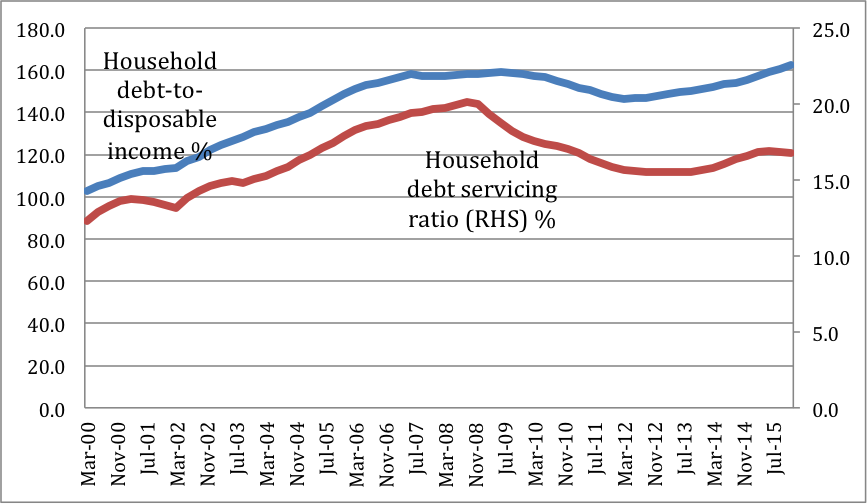

As commentators have noted, our gross national debt is nearing half a trillion dollars, largely thanks to mounting housing debt. A better indicator is debt as a % of our disposable income and that has recently increased, topping the levels seen in the last Global Financial Crisis. Only low interest rates are keeping that affordable (note below the debt servicing ratio is not at a historic high) and the question there is how long will that last? Some dairy farmers are already struggling with their debt (some 20% owe half the total debt on those farms, about $20b), and if our economy worsens then rising unemployment could mean more and more people can’t service their debts. The risk if the economy improves is that interest rates rise, and again some people won’t be able to service these debts. Either way, it is hard to see this debt binge ending well.

Kiwis prefer to borrow rather than save, so as a result New Zealand has a high external net debt. This makes us vulnerable to foreign lenders turning off the taps as they did during the Global Financial Crisis. That could force interest rates up here.

It doesn’t have to be this way

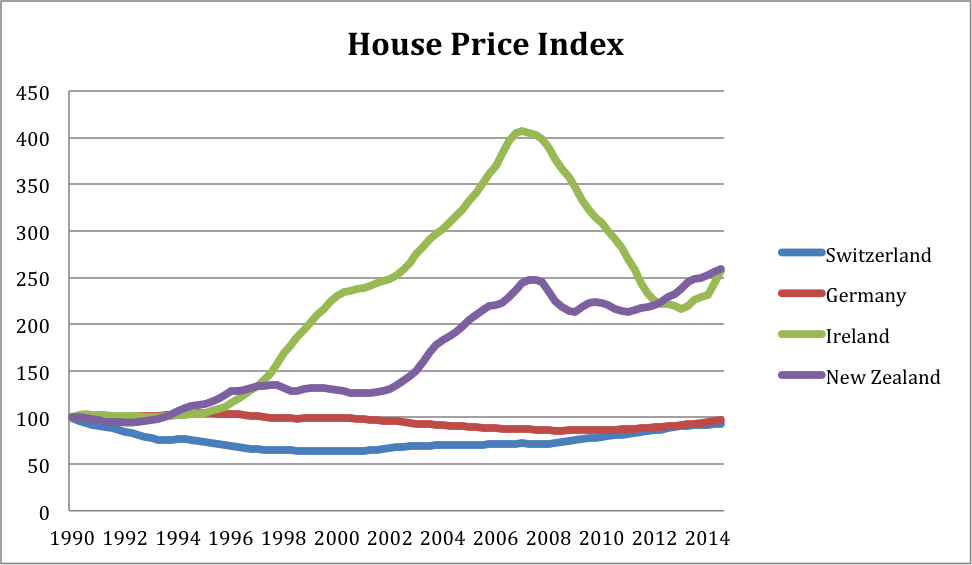

Not all countries face these issues, in fact many European countries have escaped these problems. What is the difference? Many of these countries have closed at least some of the tax loopholes on housing, and they also tightly regulate the rental market to discourage speculation. The graph below charts the different trajectories of different economies. Ireland faced an enormous bubble prior to the Global Financial Crisis, and has since deflated to about the same level as we are at now. Some countries, such as Germany and Switzerland have had flat real house prices for decades.

We don’t advocate copying these European policies wholesale – many of them are cumbersome and intrusive – but they show that restricting house price rises is possible. Implementing the Comprehensive Capital Income Tax would be a much simpler and effective way of achieving the same outcome.