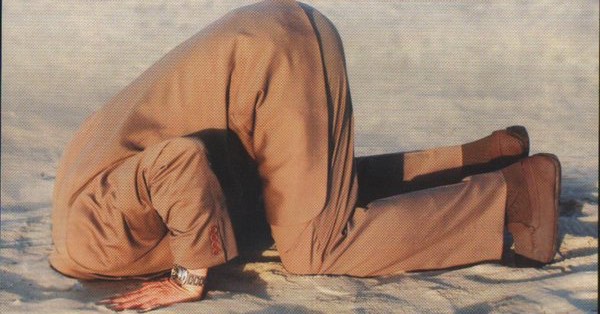

Today the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, Jan Wright, fronted up to the finance select committee to talk about the financial and economic risks of climate change, particularly sea level rise. International banks, insurers and investors have well and truly woken up to these risks and are getting increasingly vocal. Sadly, the response from our Government suggests they still have their heads in the sand.

A rising tide of risk

The Commissioner has recommended that Government convene a working group to look at issues like who pays for sea level rise, how do we plan our infrastructure and manage retreat. However, she has had no response from the Minister of Finance. Despite the inevitable nature of these risks, central government has been content to leave the problem in the hands of our many local authorities.

Dr Wright’s submission highlighted the fiscal risks of sea level rise. When combined with more extreme weather events this inexorable trend will increase flooding, erosion and rising ground water. She highlighted many vulnerable areas that could be affected in the next 50 years – particularly South Dunedin and Napier – in total some 9,000 homes with a value of $3 billion. Stuart Nash quipped that another earthquake would keep the land level sufficiently high – it was a joke, but ironically that is the extent of our planning for sea level rise.

Add in the impact on infrastructure, much of it below ground, the inevitable demand for sea walls and eventual calls for compensation from land-owners. The MPs at select committee seemed to see these as risks for property owners, banks and insurers. But insurers only insure on an annual basis, and they don’t insure for risks that are completely predictable. Government is already involved in compensating flood damage, and eventually stumped up to fund uninsured property owners in Christchurch after the earthquake. Will sea level rise really be any different?

We need to start discussing how we deal with sea level rise now, and who will pay. We also need to reshape the way we make planning and investment decisions now to avoid these future costs. Banks and insurers are keen to participate in a working group, so why isn’t the government? At the very least it makes sense to provide consistent information and guidance for property owners and local authorities to use for planning. Of course it is much easier to leave this tricky problem to local authorities to sort out.

Getting Business Match-Fit For Climate Change

Sea level rise is a key place to start, but the conversation about climate change risk is much broader. A speech last year by the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, identified three ways in which climate change will endanger financial stability: physical risks (damages from rising seas and extreme weather as discussed above), liability risks (companies and governments getting sued for the damage they have caused or allowed), and lastly, transition risks. This passage from the Commissioner’s report describes transition risks:

“Transition risks could arise if the adjustment to a lower carbon economy does not begin early enough and does not follow a predictable path. Abrupt changes in policy, for example, could trigger big changes in the values of assets. This is why the protective settings in New Zealand’s ETS might begin to damage the very companies they protect and hence the New Zealand economy.”

The transition we are talking about is to a zero carbon world (remember to keep global warming under two degrees we need to be at net zero carbon somewhere around mid-century). This is where things get messy – because for our businesses long term gain means short term pain. To get ‘match-fit’ for the climate challenge our businesses need to wean themselves off fossil fuel, starting today.

Time for a big fat price on carbon

Perhaps the biggest thing Government can do to get businesses match-fit is to put a decent price on carbon. In the words of OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurrìa, we need a “big fat price on carbon”, and the sooner we do this the better shape our economy will be in for the long-run.

There are a number of ways the Government could achieve this, but they have decided that their main policy tool is the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). However, the effectiveness of this tool is continually hampered. It is supposed to be a cap-and-trade scheme, which means there should be a limit on the amount of carbon in the system, and permits can be traded so that they end up in the hands of the person that can use it best. The two-for-one subsidy is at last being (slowly) dismantled, and the price of NZ carbon credits has recovered to $18 per tonne after crashing to almost zero due to the use of fraudulent foreign credits.

However, distortions in the scheme remain – most notably the Government has left the $25 price cap in place for the foreseeable future. There is no justification for the price chosen, no rationale. It is quite simply a price control, the sort we rile against in most markets but for some reason is acceptable in a carbon market. In 2011, the Government’s own review panel advised the Government to phase out the two-for-one subsidy by 2015 and raise the price cap each year to a level of $50 per tonne by 2017. They ignored that advice then, and five years later we are still a long way from that.

Failing to price carbon properly now will increase costs and risks in the future. A sudden jump once a crisis point hits will be a lot more difficult and painful than a smoothly rising price path. Failing to rebalance our economy over time towards clean, low-carbon activities risks loss of competitiveness. Investments in high-carbon industries today risk becoming stranded assets and financial losses tomorrow.

What should the price of carbon be? So far, the Government hasn’t done the analysis on what kind of carbon price path we would need to meet our 2030 emissions target (the stuff they did release was too full of holes and poor assumptions to be of any use). Given the recent cuts in policy advice on climate change, we shouldn’t expect that work to be done anytime soon.

Thankfully the OECD can answer some of our questions. For the world to be on a pathway to less than two degrees of warming, most studies indicate the global average carbon price would need to rise to around $80-120 USD per tonne by 2030 (say roughly $150 NZD). A different question we can ask is what is the cost of the damage caused by a tonne of CO2 emissions. This ‘social cost of carbon’ is complex to assess and depends on how we value the future. The US EPA uses a central figure of around $60 NZD per tonne today (this will rise over time). Some studies put it much higher – in the range of $75 to $235 NZD.

Of course the politics of rising carbon prices is tricky. If the Government isn’t prepared to let the price rise like it needs to, there are other ways to increase the effective price on carbon. Many countries in the world have far higher taxes on fuel, for example.

In a nutshell, ongoing dependence on fossil fuels and other high-carbon activities is a risk that will grow in the future. Pricing carbon properly today is part of derisking our economy and growing our competitiveness in a carbon-constrained future.