Why German House Prices have been Flat

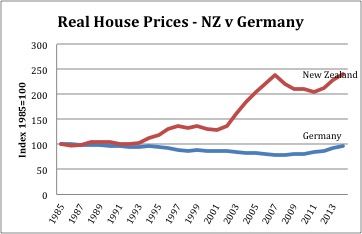

The picture below says it all – German house prices have been flat (in real terms) for the past 30 years, while over the same time ours have increased by 150%. This despite the fact that Germany is the one of the most successful economies in the world and their per capita incomes have risen faster than those of New Zealanders. Why is that, why have we lost the plot and what can we learn from them?

History

History plays a big part in all of this. Europe suffered two world wars, which destroyed an awful lot of houses. After WW1 the State generally led the rebuild. After WW2 it was a more mixed picture – State and cooperative led in the East and a mix of private, State and cooperatives in the West. Housing is seen as part of the country’s infrastructure, rather than a sector pretty much solely for private endeavour. That’s a huge difference from our culture, but the German value is that everyone should have a reasonable quality roof over their head. They don’t have to own it, but rents are very much controlled in favour of the tenant.

Housing cooperatives are a bit like Fonterra; they are regulated by the government and owned by members (who own shares). Some of the members are residents and some of which are not; like Fonterra the non-residents get a nominal dividend but can’t vote. They first appeared in the 19th Century, and still play a major role in providing affordable housing for sale or long-term rent across the country. There are over 2,000 cooperatives in play today, owning over 2 million rental units. Some cooperatives offer other services, like kindergartens for families or nursing for the elderly.

Various policy settings have played an enormous role in averting speculation too, covering price controls, taxes and planning.

Price Controls

The German government has a history of getting involved in the market whenever the private sector gets too out of control. After the re-unification in 1989/90 there was a law that controlled rapid house price rises to a maximum of 4%, and any capital gain had to be the result of investment made in improving the property. This policy effectively killed speculation post re-unification.

Current policies are not quite that heavy handed, but they aren’t far off. There are strong regulations that benefit renters and limit the gains that can be made by investors; there are rent controls, and as long as renters pay the rent it is very difficult to evict them. The downside is that rental controls have removed the incentive to build new properties, so the state or region has sometimes had to offer incentives to build where there are shortages.

Taxes

They have a tax (also known as a stamp duty) of between 3.5%-6% (depending on the region) of the property value every time it changes hands. If there are any capital gains left after that, they can also be taxed! Now this doesn’t mean we should rush out and have a stamp duty and capital gains tax (CGT) – we’ve talked about their problems before. In particular transaction taxes such as stamp duty or CGT are less efficient than recurrent taxes such as the Morgan Foundation’s proposal of a Comprehensive Capital Income Tax.

The Germans also have a tax on property values that is similar to a mix between rates and a land tax or the CCIT that we have proposed. Nowadays the tax is quite low, as property values haven’t been updated for inflation for many years. However, its existence is an important deterrent to speculation – the tax isn’t needed if price inflation doesn’t exist!

House prices have also been very stable in Switzerland, and many regions have similar policy settings to Germany. There is a tax on imputed rent in Switzerland, which again is very similar to the CCIT. These sorts of taxes reduce the tax advantages of owning a home over renting one, which explains why Germany and Switzerland have the lowest home ownership rates in the developed world.

Planning

All land sales are scrutinised by committees, and experts advise on what the property is worth and what property can be used for. This provides transparency for buyers and sellers that gives an orientation/ guidance for the price of land in an area.

As pointed out by the NZ Initiative in their report Different Places, Different Means, local councils in Germany and Switzerland benefit from developing more housing as when their population rises their funding increases. NZ Initiative postulates that this incentive encourages development, which keeps prices down. Essentially councils are competing to attract people and businesses.

Culture

These policies and history have given rise to a culture where the Germans are simply not obsessed with owning their own home. They are happy to rent for long periods if not their entire life, and certainly don’t see investing in rental properties as a get rich scheme. Property is a place to live, nothing more.

The Germans have the 2nd lowest ownership rate after Switzerland. Since 1999 the Germans have seen some speculation on their property, but generally that has come from overseas, particularly pension funds, rather than locals.

Economic Benefit

Both the Germans and the Swiss rightly see the way to get rich as investing in profitable businesses so that they can export to the world. This culture of non-speculation is quite the opposite of New Zealand where speculation is a national pastime, a culture that is aided and abetted by our tax and policy settings.

We may despair at the low rates of home ownership in Germany and Switzerland, but by reducing speculation in housing this frees up money to go where it is needed – investment in businesses. This is precisely what is better for the national benefit – over-investment in property just bleeds the economic growth rate.

To summarise – the Germans have policy settings that encourage the population to see housing as providing shelter, and as part of their basic infrastructure, rather than an investment. This is driven by policy. The policymakers have known for a long time that true prosperity comes from investing in business and generating income and employment – not setting policy to encourage people to bid up the prices on the same property year after year. That’s not wealth creation – it’s wealth redistribution.