Two weeks ago Climate Change Minister Paula Bennett announced her intention to ratify the Paris climate change agreement before the end of this year. This is great news! There is strong momentum behind bringing the agreement into force as early as possible, and it’s positive for New Zealand to be part of that.

However, there are reasons to be cynical. The main reason the Government is so eager to ratify early is to avoid being shut out from the rule-making process. Rules around forest carbon accounting and international carbon markets are still up for debate, and these are the key ways New Zealand has delayed and avoided meaningful action to date. Our concern is that the Government will do everything it can to bend the rules in NZ’s favour to again minimise the need to actually do anything real to meet our 2030 target.

Dumping the junk

The first way the Government might seek to cheat is by ‘carrying over’ its stash of surplus carbon credits and using these towards our 2030 target. Minister Bennett has laughably claimed that these surplus credits are “clean”. In reality, as we explained last week, the Government only has that stash because of the huge quantity of fraudulent ‘hot air’ credits it used to meet our earlier commitments. The Government is effectively laundering junk credits and perpetuating the fraud.

Minister Bennett has so far refused to commit to cancelling the junk credits by 2020, and her language suggests that she wants to keep exploiting them to the maximum degree possible. If the projected surplus of 85.7 million credits were to be carried over, this would cut more than 1/3 off the emission reductions New Zealand would need to make to meet the Government’s 2030 target.

The Paris agreement states that any carbon trading must, of course, ensure environmental integrity. New Zealand has not done this in the past, so carrying over past credits would make a mockery of this. Minister Bennett needs to do the right the thing and dump the junk.

How much use should we make of carbon markets?

The Government has made New Zealand’s 2030 target entirely conditional on unrestricted access to international carbon markets in the future. To our knowledge, New Zealand is the only developed country to have done so.

Given our Government’s track record of negligence at ensuring environmental integrity in our carbon market, this does not bode well – especially when the Paris agreement gives more free reign than the Kyoto Protocol did. The Government needs to do two things at the very least: first, it should properly explore the costs and benefits of meeting the proposed 2030 target through domestic action alone. Second, it should use that analysis to place a limit on how many credits can be imported, so we have to reduce emissions domestically and progress towards a zero-carbon economy.

Tricksy accounting

The third – and potentially most significant – trick up the Government’s sleeve is to fiddle with the carbon accounting rules for forestry. This accounting is horrendously complex, which makes it prone to manipulation. Because we are a small population with a lot of land, forestry has a much bigger impact on New Zealand’s net emissions compared with other countries. Accordingly, New Zealand works hard in international negotiations to deliver forestry rules that are favourable to us.

The forestry accounting rules applied in the Kyoto Protocol have so far worked heavily in New Zealand’s favour. The record planting boom in the 1990s planting boom established several hundred thousand hectares of new pine forests that have been in their growth phase. These trees stored enough carbon to offset New Zealand’s 20% emissions overshoot for the 2008-12 Kyoto period. They are similarly helping towards our 2020 target, with dodgy foreign credits filling the gap.

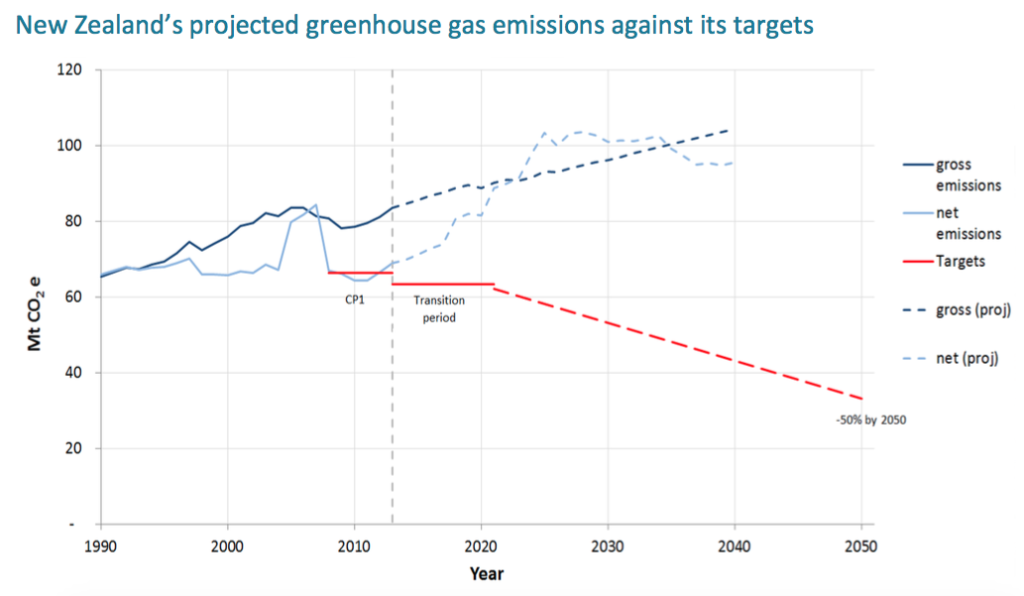

But there’s a catch: much of that carbon will be released again when the trees are harvested. The Government has sat back and relied on temporary carbon storage, in effect putting the bill on the credit card until the next decade – thanks very much, guys. The trouble is that the time to pay the bill is arriving. The graph below, from the Ministry for the Environment’s 2014 briefing to the incoming ministers, shows what this looks like (observe how the light blue ‘net emissions’ line climbs steeply).

So, what is the Government’s response? Having benefited in the good times, they are now pushing to change the rules. They intend to switch to an “averaging” approach, which will completely remove the planting and harvest cycle once a plantation forest reaches maturity. This change actually seems sensible; the problem is that we are changing the rules halfway through the game, in a way that directly favours us. If we had used the proposed rules from the beginning, New Zealand would receive far fewer forestry credits up to 2020.

This sneaky rule change will weaken what New Zealand’s 2030 target actually means in practice. We don’t know by how much, because the Government won’t tell us – or anyone else for that matter. The Morgan Foundation attempted to get the data through an Official Information Act request, but it has been withheld with the excuse that this would disadvantage New Zealand in the international negotiations. Yes, our emissions projections are officially a state secret. Make of that what you will.

Economic analysis deeply flawed

So, we’ve described one part of the strategy: minimise the actual emissions reductions required to meet the 2030 target. Another part of the strategy we have discussed before: exaggerating the costs in order to argue against a stronger target.

Last year’s economic modelling has been rehashed in the National Interest Analysis of the Paris agreement. This claims the 2030 target will reduce annual disposable income by 1.2% (n.b. it would still grow by about 34% compared to today). We have discussed the many flaws in this analysis in blog posts last year. At least the NIA admits that the quoted cost estimate is “at the high end” and that important benefits have been ignored. But really, this doesn’t begin to describe the problems.

The reality, in our view, is that the numbers the Government is citing are completely meaningless. Two key reasons are the absurd baseline scenario and the fact that New Zealand has done almost nothing to reduce emissions so far. Assuming New Zealand isn’t going to walk away from international agreements altogether and change our national slogan to “100% Immoral”, the question is what target to take on, not whether to take one. The meaningful thing to look at is therefore the difference between potential targets.

The Paris agreement affirmed the principle of ‘progression’, so it is quite clear that the minimum target New Zealand could have is 5% below 1990 levels by 2030 (i.e. the same target level we have already set for 2020). A weaker target would risk similar impacts to not joining the agreement at all. Relative to this, the modelling says the Government’s current target (an 11% reduction on 1990) would reduce Real Gross National Disposable Income by just 0.09%, at the high end. This is small enough to be a rounding error. Even for a target of -40% (equal to what the EU is promising), the modelling says the impact would be less than 0.5%.

How to take the Paris agreement seriously

A recent Dominion Post editorial summed it up best:

Enough of the obscure rules and the clever accounting: if New Zealand can’t be a champion for tackling climate change properly, few countries ever will be.

The Government seems intent on continuing its old games to enable a bare-minimum response to climate change. Not only is this doing our country damage in the long-run, it is ignoring the real essence of the Paris agreement: the transition to a zero-carbon world in the second half of the century. We need a clear long-term plan and policies to get on track, ideally backed up by a legislative framework such as the UK Climate Change Act.

Parliament is currently taking submissions on examination of the Paris agreement. You can make a submission here by Friday 2 September.