How many families with children find themselves struggling with rising costs in New Zealand?

According to research by Statistics New Zealand in 2009, over half of New Zealand families experience at least a year of income poverty after the arrival of a child.

It is helpful to use a kete of measures to assess family resources. In 2016 around 27% of New Zealand’s just over a million children lived below the ‘income poverty line’. What about material poverty? Children’s basic needs?

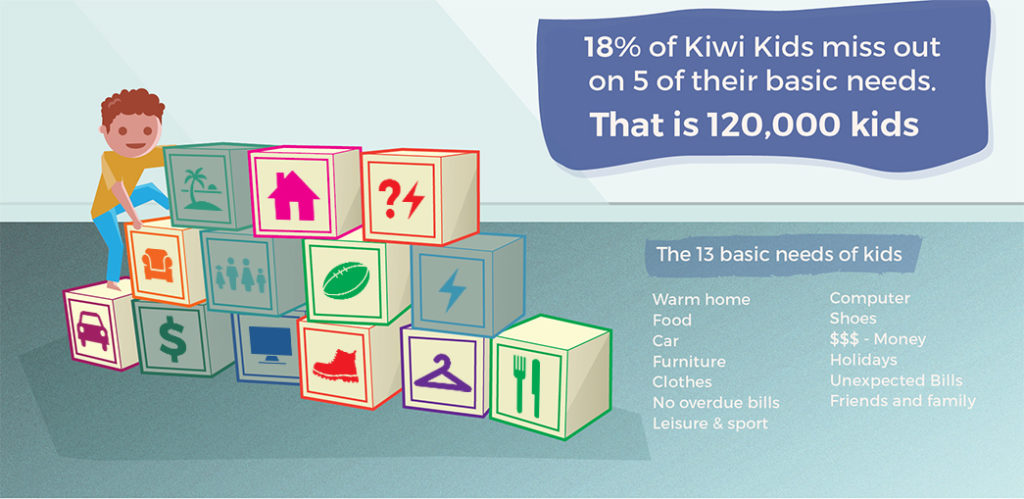

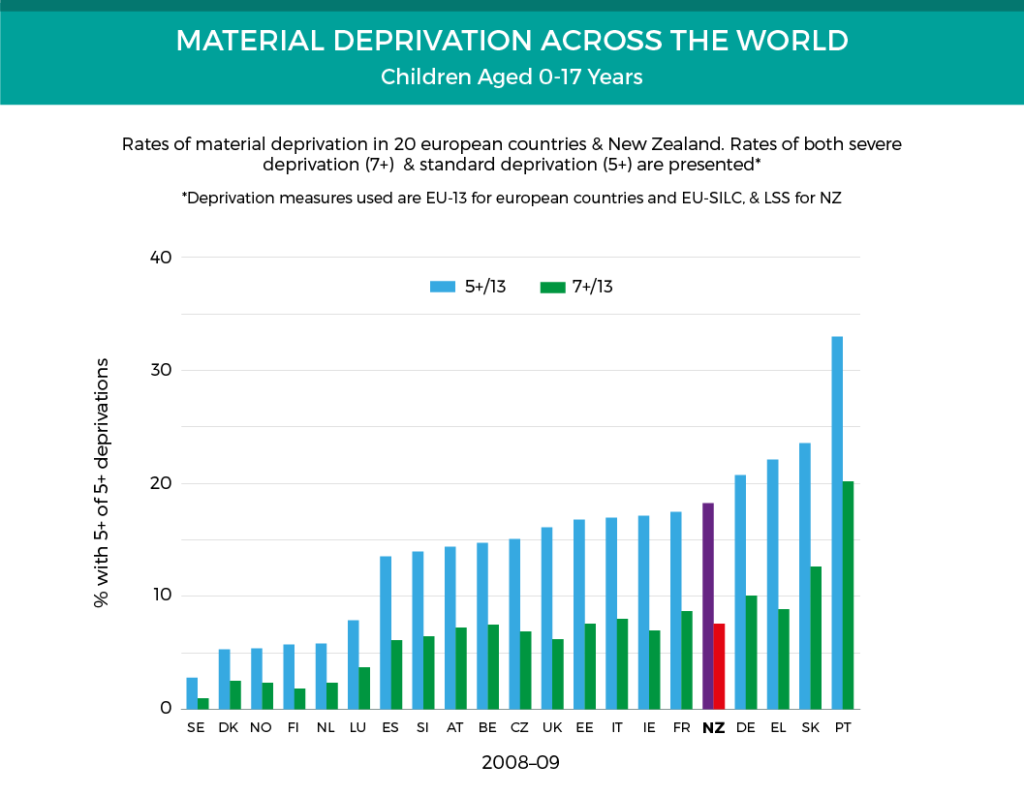

In 2016, 18% of children in New Zealand missed out at least 5 of their 13 basic needs.

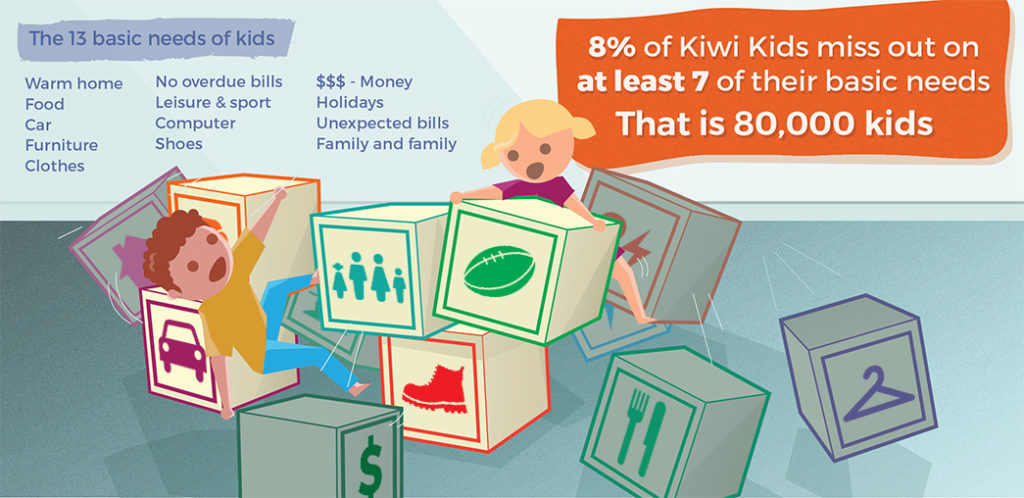

In 2016, 8% of children missed out on at least 7 of these basic needs.

Have we always had the same rate of struggling families?

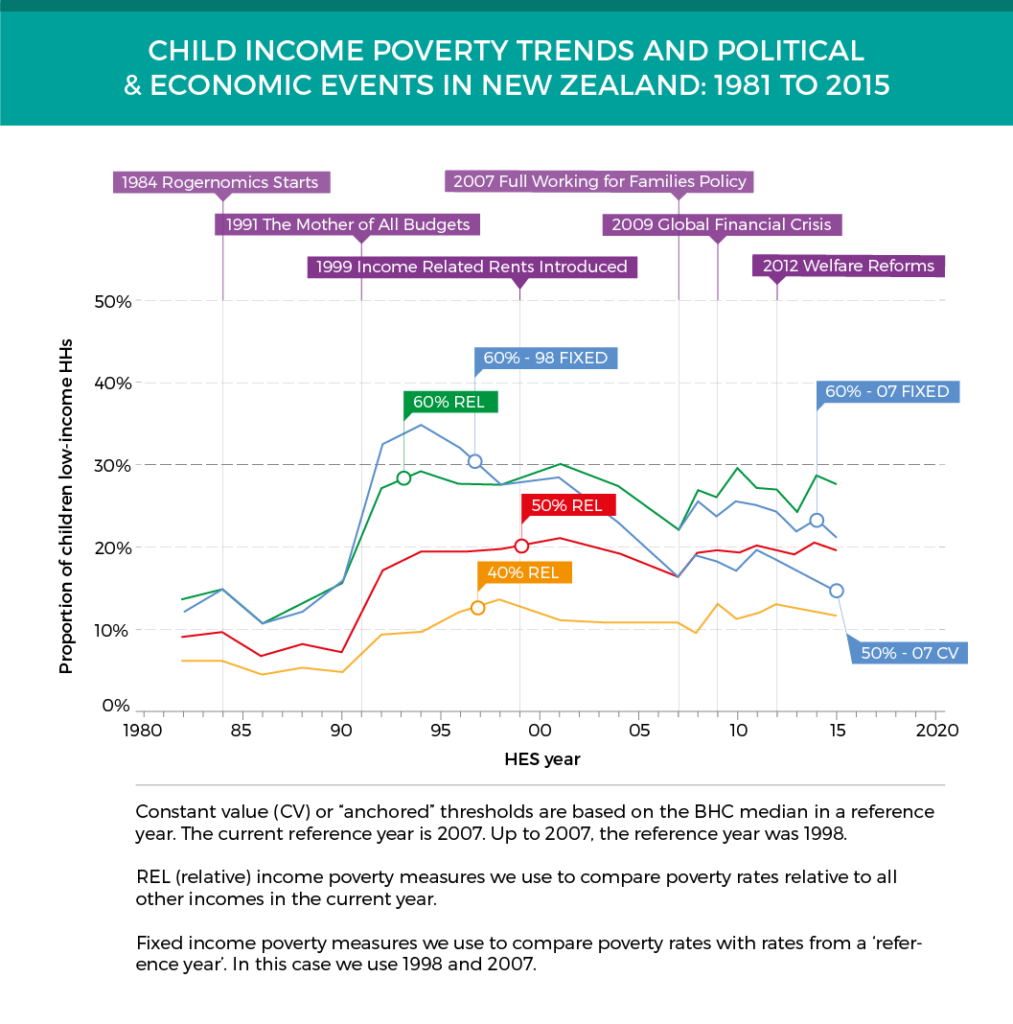

No. Rapid economic deregulation in the late 1980s lead to large-scale unemployment. In 1991, this was followed by massive cuts to social welfare payments, including the universal family benefit that had been in place since 1948. At this point family income poverty leapt. We have not righted the imbalance that was created since.

Here we can see what has happened in terms of income poverty for children since the 1980s.

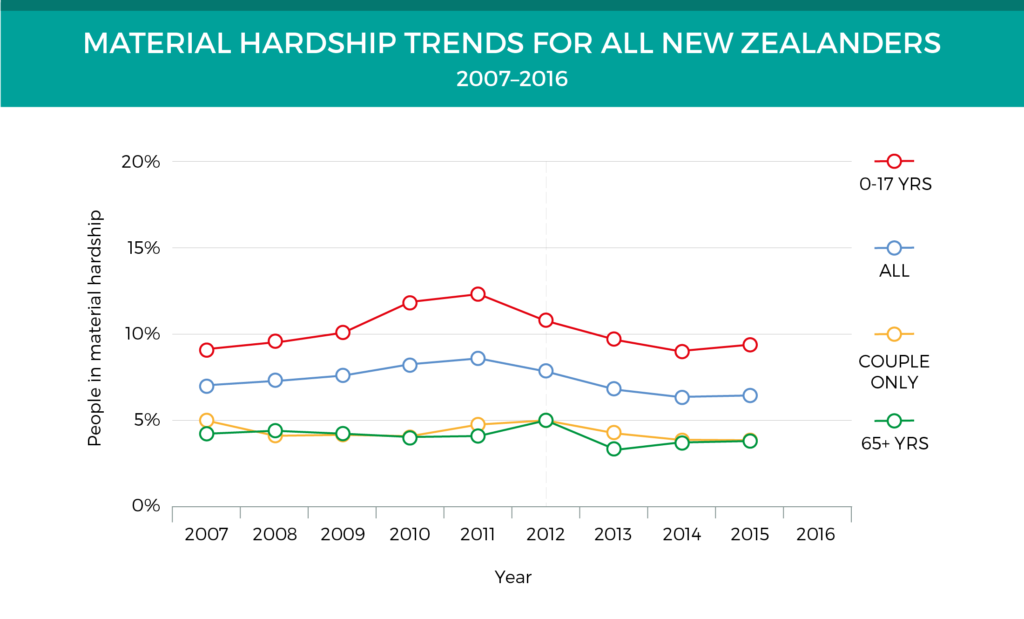

Material measures of poverty (a measure of unmet basic needs) show a similar and consistent pattern since we started measuring in the mid 2000’s: Families with young children are struggling.

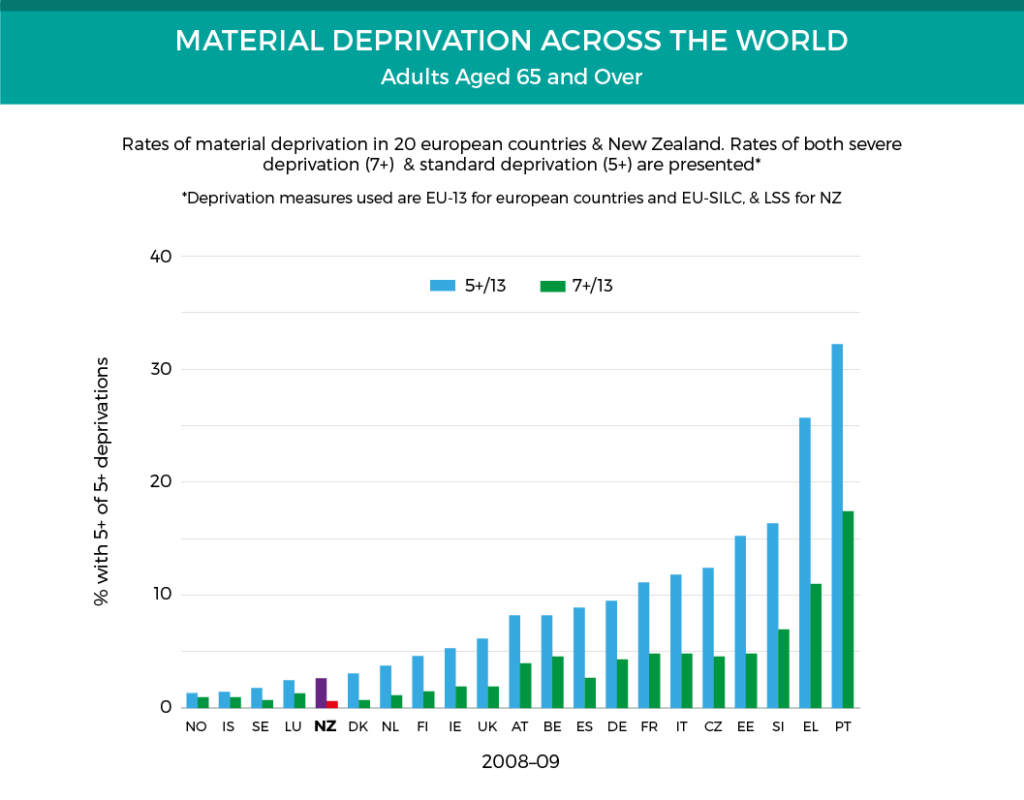

What has not changed over the same period is the universal payment we make to those aged 65 and older. The protective effect of superannuation and house ownership on the elderly is clear; older New Zealanders do well internationally. Children do not. Cash payments make a difference.

And it is not just about income or basic needs.

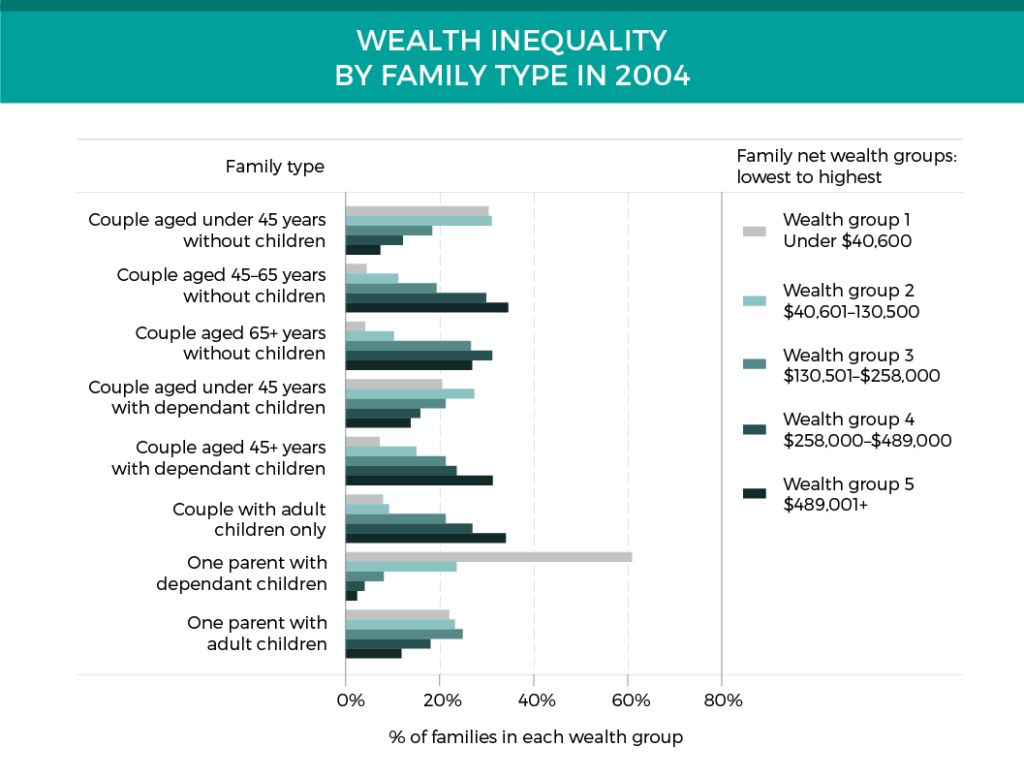

Families with younger children have less wealth, and sole parent families have the least. This leaves families with less of a safety net during any years of low income.

Who are the families that are struggling In New Zealand?

The risks of becoming or staying poor are higher for certain family types. For example, while two thirds of children in New Zealand live in two parent families, 53% of children living below the income poverty line live in a sole parent family. That means that 47% children living below the poverty line live in two parent families. Sole parent families are at greater risk of being poor because they are primarily headed by women, and women parents have the lowest incomes in New Zealand.

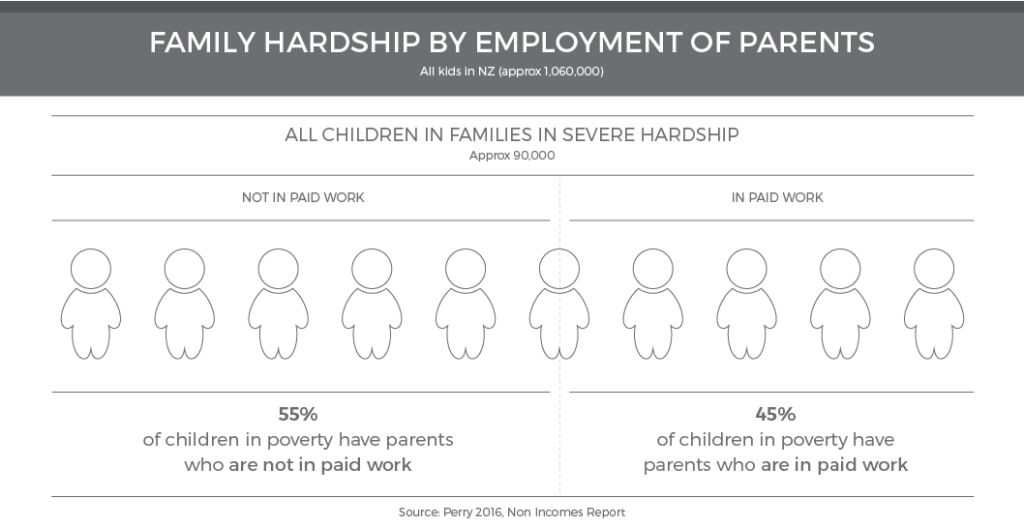

The story that the data tells is that the risks of being poor for certain family types are higher, but that the families who find themselves poor are very diverse.

A near equal number of children in hardship have parents who are in paid work as are not in paid work.

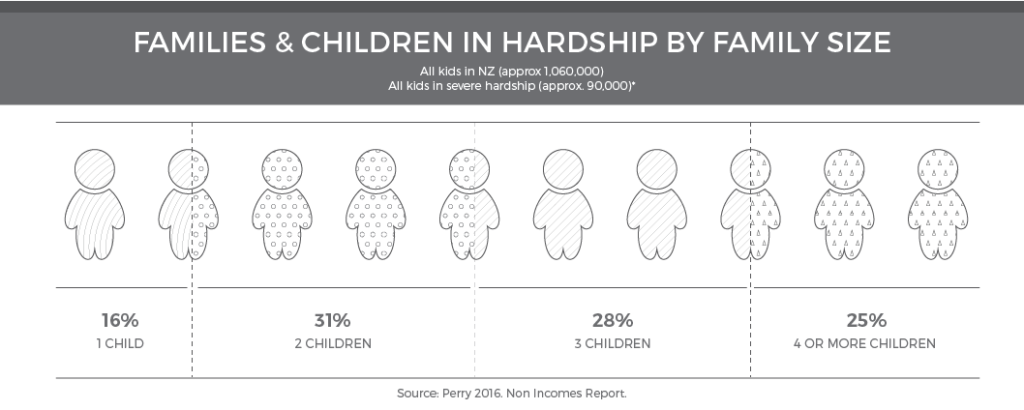

Around half of children living in hardship come from a family with only one or two children.

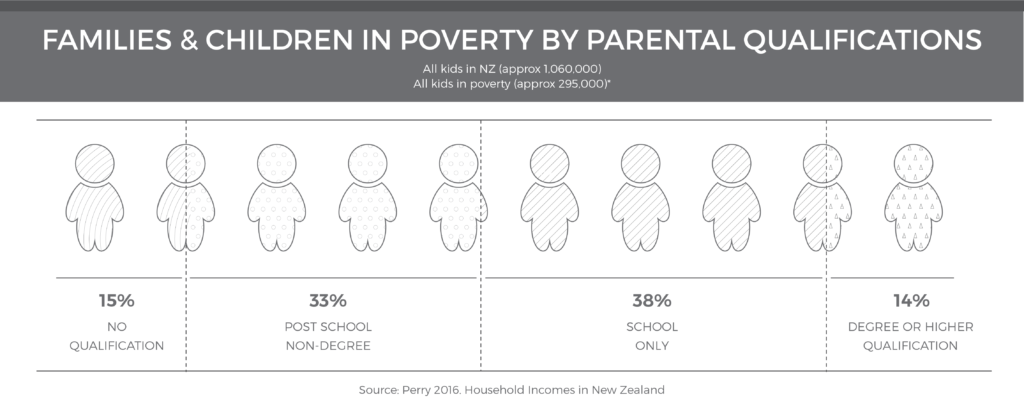

Children in income poverty have parents with a range of educational qualifications. A post-school qualification or degree does not protect families from being poor.

The data tells us that families who find themselves poor are families like ours. It is what happens to families in New Zealand when they find themselves poor that is the issue we need to address first if we want all children to thrive.

In Pennies from heaven we discuss the stress impacts of low income, why stress is a universal experience for families who find themselves under pressure, and how policy can be used to lift this for families who find themselves poor and improve the lives of their children.