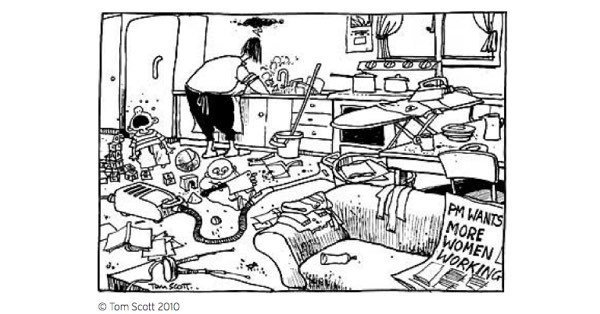

In the last few days a thoroughly researched report by the Brainwave Trust has summed up the evidence regarding the risks and benefits of early childhood care/education (ECE). Despite concerns that the conclusions are scaremongering and the fact that Family First have decided to use it as yet another piece of four by two to beat parents (notably mothers) over the head with for not staying at home in the kitchen, the report highlights a growing reality for many families in NZ. These realities are: 1) that using early childhood care is not real choice for many parents, 2) that fulltime ECE before age one has some obvious risks and 3) low quality childcare is not linked to the benefits that are often talked about by policy makers and politicians. In our own research we could find little to support the often-lauded benefits of ECE unless a set of ideal circumstances are met (many of which are determined by the relative wealth of the family and the area they live).

However it is Not the Parents’ Problem

We don’t believe the solution to these issues lie with parents at all. Suggesting that parents should use the findings to weigh up these risks and benefits and make a clear choice belies the reality of an entire system of broken housing, labour market, welfare, social and early childhood education policy that needs fixing.

So without further ado here are 10 ways we could fix the problem without telling parents they need to think harder (read ‘feel guilty’) about what happens to their children when they go to work.

- Fix the housing crisis. The massively inflated cost of housing compared to incomes (in all income groups and especially for those with the least) is driving many parents into a situation where parents NEED to work simply to keep their heads above water and stop falling below the poverty line. We have suggested some of the solution lies in tax reform. A stronger, more strategic (actually any strategy at all would be good) social housing approach would also be really useful.

- Stop squeezing the funding of ECEs, so that only those ECEs in wealthy areas (where parents can afford to pay fees) can do all those things that make a place high quality. For example achieve a high ratio of qualified teachers to children, low numbers of children, buy toys, and learning equipment, nappies and food for the kids, and purchase a safe and relaxed physical environment.

- Reconsider whether profit making is the right model for ensuring the highest quality best outcomes for children in ECE.

- Ministry for Education should not only be using rates of attendance at ECE as a target, they need to start assessing meaningful outcomes for all children, like well being, preparedness for school, health etc.

- Recognise the real value of parenting to the economy via a Universal Basic Income. Unpaid work (which also includes voluntary work) was valued at $40 billion to the NZ economy in 1999 (39% of GDP), 64% of this value is attributed to work done by women, most of which involves caregiving for children and the elderly. When Canada undertook a UBI experiment in the 1970s the biggest effect they saw was that women delayed paid work (they did not withdraw from the work force) until after their child was one.

- Stop punitive, conditional welfare policies that push sole parents into paid work and their children into low-quality ECE, all while claiming benefits to attending ECE and having these parents in low paid work that simply are not there.

- Improve labour and workplace policies that actively encourage and support men to take on the role of parenting at home in equal measure to women. This would have the additional bonus of helping close the gender pay gap which in turn would mean the pure economics of pay were not the deciding factor for women to do the caregiving.

- Invest more heavily in ECE in low-income areas, where both the quality and sufficiency of centres is of major concern.

- Allow those who receive a benefit (especially those with children) who also do work (of which there are many) to keep more of their benefit. This would ensure that those people who can only get casual, non permanent or otherwise insecure low paid work have more income security and are not constantly facing having their benefit cut and their family income going to zero overnight. This would reduce the use of low-quality casual childcare and probably incentivise work more.

- Remove the punishing effective tax rate on work over 20 hours on Working For Families (WFF). And remove the minimum work requirement of 20 hours to qualify for WFF. For sole parents on minimum wage for example every $1 earned after 20 hours worked is effectively taxed at near 100% (so not worth doing once costs are taken into account). If work is less than 20 hours (in any 3 week period) they no longer qualify for WFF at all. Parents must then find a job that is exactly 20 hours (no more no less) and line up childcare to match. While 20 free hours of childcare is available for children over 3 (which in many centres is actually only a partial subsidy of fees charged) this does not account for travel time between work and the childcare, which needs to be paid for in full.

So there are some ideas, not rocket science really. It seems that yes there is a crisis in childcare in this country, but that is because there is a terribly narrow approach in our policies that affect families and children. No one appears to be measuring what policies actually improve outcomes for the next generation. Instead of focusing on actually might work for children and families we are focused instead on what works right now to save a bit of cash and meeting some ideological beliefs about WHAT work is valuable and WHO makes good parents.