The international organisation that reports on the economic wellbeing of developed countries delivered us a stark message last week:

“New Zealand’s growth model is approaching its environmental limits. Greenhouse gas emissions are increasing. Pollution of freshwater is increasing across a wider area. And the country’s biodiversity is under threat.”

This was from the OECD ten-yearly Environmental Performance Review of New Zealand. The report provides a critical overview of environmental trends and policy issues, and recommends a raft of solutions. There a few bright spots, but for anyone who doesn’t think we have serious problems, the report ought to snap them out of complacency.

Most interesting to me was how they framed things. The first sentence above cuts to the heart of why New Zealand is struggling to deal with our escalating environmental problems: these are being traded off in the pursuit of an outdated growth model.

The current model: sell more stuff?

What is New Zealand’s growth model exactly? As the report puts it, one that is “largely based on exporting primary products”. The OECD diplomatically trains its crosshairs on the Government’s Business Growth Agenda and its goal of increasing exports to 40% of GDP by 2025. This has in turn led to the hefty goal of doubling primary industry exports (in real dollars) between 2012 and 2025.

To its credit, the Business Growth Agenda aims to increase value-add and “improve productivity while reducing environmental impact.” The problem is this isn’t working. As the OECD report highlights, our environmental performance is getting worse. (Meanwhile, as we discuss below, New Zealand is falling further behind most OECD countries on economy-wide productivity.)

The reality is that, for all the talk about focusing on value-add and productivity, government policies are encouraging more exploitation of natural resources at the expense of our environment.

Burning the house down to keep warm

When we don’t recognise the real value of nature and healthy, happy societies, we end up with growth that looks good on paper but doesn’t necessarily improve our living standards. We end up eroding our natural capital and social capital. These natural and social assets underwrite a healthy economy over the long-run and have intrinsic value that we should be aiming to protect – and to grow.

At worst, we can end up with ‘growth’ that actually makes us worse off – “uneconomic growth”, or as we have called it in the past, “dumb and dirty growth”.

An example highlighted by the OECD is the Government’s financial support for irrigation schemes, which will very likely lead to further dairy intensification and increased pollution. We saw another example just last week with the Government opening up the shores of Lake Te Anau for oil & gas prospecting. This is all part of the drive to grow commodity exports.

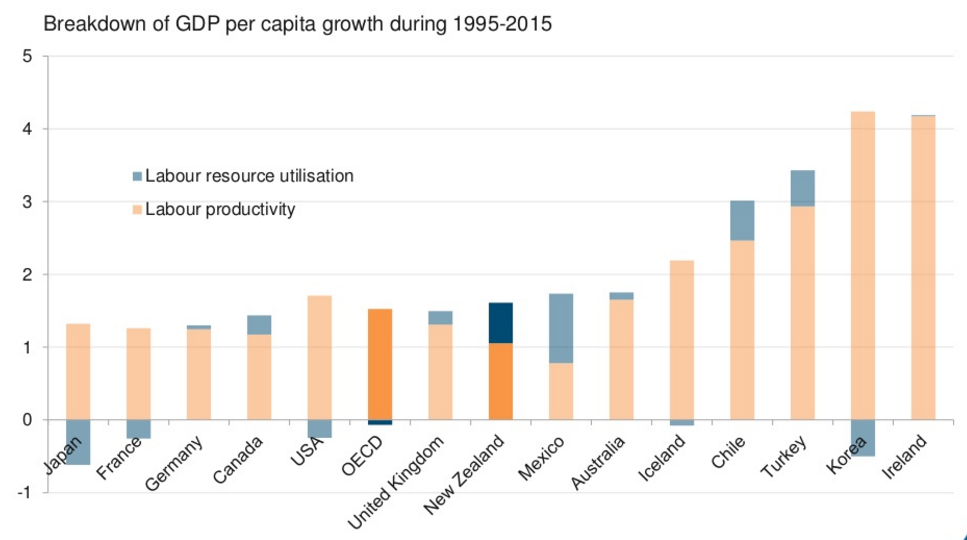

The problems here aren’t just about the environment. When we dig beneath the surface, our current growth model is delivering poor economic outcomes too. The graph below, from OECD Environment Director Simon Upton’s launch presentation, shows how New Zealand’s labour productivity growth over the last two decades is well behind most OECD countries. We have ‘kept up’ through more people working more hours. (This trend is the reason the Productivity Commission was established in 2011 – an ACT Party initiative.)

If that looks bad, the more recent trend is terrible. In an excellent article last week, Bernard Hickey reports that real GDP per hour worked has stagnated since 2011, and has actually gone backwards in the last six months:

“Essentially, more people worked many more hours to increase output. That’s not a rock star economy. That’s a cover band economy.”

More people working longer hours while our environment deteriorates? This is a broken model rooted in last century’s thinking. So what can we do to turn things around? Here are a few ideas.

Changing what we measure

A tunnel-vision focus on crude GDP and export numbers obscures the full story of how we are going as a country. We need to change what we measure and broaden our definition of economic and societal progress. (As my colleague Jess wrote about recently, this should include measuring and valuing the enormous contribution that unpaid work makes to our economy.)

Last week Parliament voted on a private member’s bill from the Green Party’s James Shaw that aimed to do exactly this. The bill would have introduced a set of ‘Sustainable Development Indicators’ into the public finance reporting that occurs with the annual Budget. The bill failed its first reading, with National, United Future, ACT and New Zealand First voting against it. This is a real shame, to put it mildly – particularly when all MPs who spoke endorsed the bill’s general principles.

Similarly frustrating is Treasury’s Living Standards Framework. The framework itself – which emphasizes looking beyond just GDP and incomes to sustainability, equity, social cohesion and risk management – is good. However, after years in development it has languished in implementation due (we can only assume) to lack of political will.

Changing what we tax

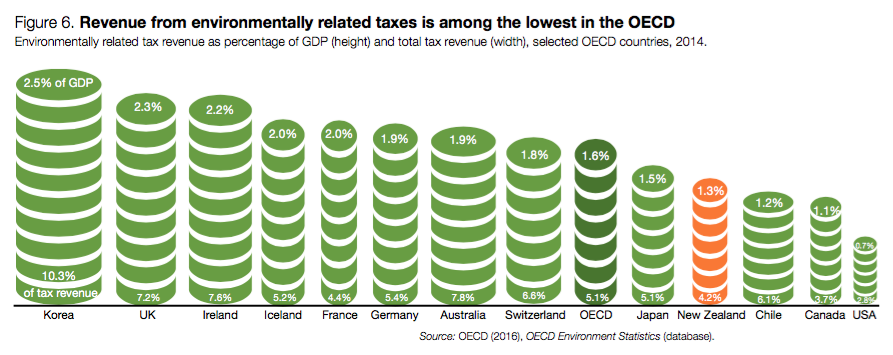

The Morgan Foundation has talked a lot about the imbalances in our tax system, particularly how we under-tax wealth and over-tax income. The OECD report highlights that our environmental taxes (primarily on fossil fuels and carbon) are also among the lowest in the OECD. This is related to why we are among most energy-intensive and emissions-intensive economies.

Shifting taxes from ‘goods’ (such as income) onto ‘bads’ (such as fossil fuel and water consumption) is a key part of building a cleaner economy. Doing this helps to drive efficiency, spur greater investment in low carbon and other green technologies, and shift consumption patterns. We could also use the revenue from environmental taxes to further incentivise better alternatives – for example, taxing gas guzzlers and using the revenue to subsidise more efficient cars or critical public transport infrastructure.

Changing the conversation

We need to get better in New Zealand at having conversations about long-term transitions. We saw this last week, when suggestions of lowering livestock numbers over time in Vivid Economics’ Net Zero in New Zealand report lead to hysterical headlines about “slashing herd numbers”. The prize for the best cow-loving hysteria of all must go to Kiwiblog’s David Farrar with “MPs want to kill one in three cows” (wrong in fact as well as presentation).

We need to get past knee-jerk responses like these if we want a sensible debate about New Zealand’s climate change response and other long-term issues. The report in question was talking about scenarios for New Zealand in 2050, one of which had sheep and dairy populations 33% and 20% lower than today respectively. For perspective, New Zealand’s sheep population has fallen by 60% since 30 years ago while our plantation forest estate grew by about 50%. The point is that land-use in New Zealand is very dynamic, and we are talking about a gradual transition. That doesn’t mean MPs with knives sneaking up on unsuspecting cows. It means changing policy and investment signals to drive the desired change over time.

(And David, don’t worry, I’m pretty sure the cows alive today will be long gone by 2050 regardless of what our MPs do.)

Changing the paradigm

New Zealand’s current growth model has us stuck in the false dichotomy of “economy vs environment”. New Zealanders are clear they care about environmental protection. But action to respect environmental limits is in conflict with the Government’s economic agenda. Either we change the agenda, or our environment will continue to deteriorate.

Research shows us that there are better ways to drive our economy if we choose to do so. Earlier OECD research has shown that “stringent” environmental policies can go hand-in-hand with a thriving economy. Indeed, over the last 20 years, most OECD countries have reduced their pollution levels and improved their productivity more than we have.

The OECD’s review brings all of this into focus. We need a new model for green growth that puts environmental wellbeing at its core. Chucking out the Business Growth Agenda might be a good place to start.